There Was Once A Village

The Story Of Sitchel And The People Who Called It Home

Foreword

Dear Fried Family,

I never knew much about the Fried family history. The following is a translation and collection of ideas from the book given to me by Totty, "Geven a mool a derfel" (There Once Was a Village), about the town of Sichel where our great grandparents lived before coming to America. It was eye-opening for me, and I hope it will be for you as well. We have a lot to be proud of and to live up to.

This content is heavily generated by AI. I spent alot of time to check it, clean it up, and enhance the content, but I definitely cannot vouch for factual accuracy. Please treat this as a family and historical project that may contain errors, or even complete fabrications, and not a final scholarly edition.

If you’re short on time:

Here are the chapters I think a Fried should read even if you don’t get through the whole book.

• Chapters 1,2, and 3 (the chapters that describe Sichel itself):

read these to understand what kind of place our family came from—its geography, economy, daily rhythm, and what Jewish life looked like in a rural mountain village.

• Chapter 9:

this is the core “Fried chapter” in the Sacel narrative, and the place where R’ Avigdor Moshe Fried is portrayed most fully in the story.

• Chapters 10, 11, and 12 - The war chapters:

read these to understand how the entire world of Sichel ended—what changed under Hungarian rule, what happened in 1944, and why so much of this story has no natural continuation.

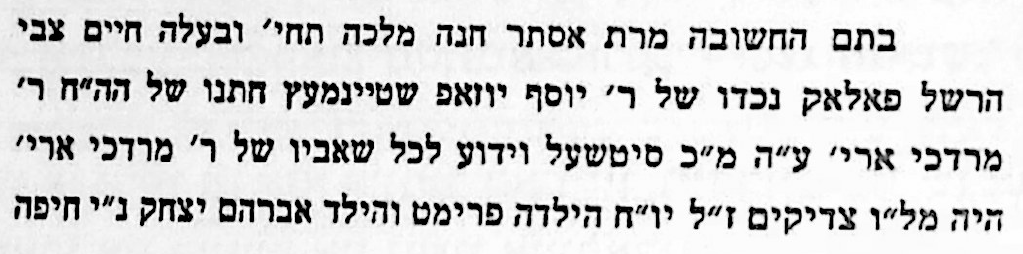

People & Lineage

The Family Tree

- Totty: R’ Avigdor Moshe ben R’ Shlomo (married to Bubby Fried) AM’sh.

-

Zaidy Shlomo: R’ Shlomo ben R’ Avigdor Moshe (Totty's father).

- Spouses: Married to Chaya Sara Kizelnik (in Europe) and Grandma Malka Satler (in the US after the war). (There is a Kizelnik now living in SI that is a direct descendant of her.)

-

Yahrtzeit: 8 Shevat (Ches Shevat).

- Niftar: Shabbos Parshas Bo, 5720 (February 6, 1960).

-

Uncle Mendel: R' Yitzchak Menachem ben Shlomo (Zaidy Fried’s brother).

- Yahrtzeit: 25 Cheshvan (Chaf Hei Cheshvan).

- Family Status: He was the only son of R' Shlomo to survive the war (Totty and Tante Hadassah were born later in America).

- Life & Vocation: He used to assist his grandfather, R' Avigdor Moshe, in the slaughterhouse in Sichel. Later in life, he carried on this tradition and became a respected Shochet in Boro Park.

-

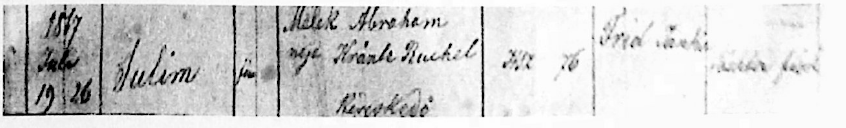

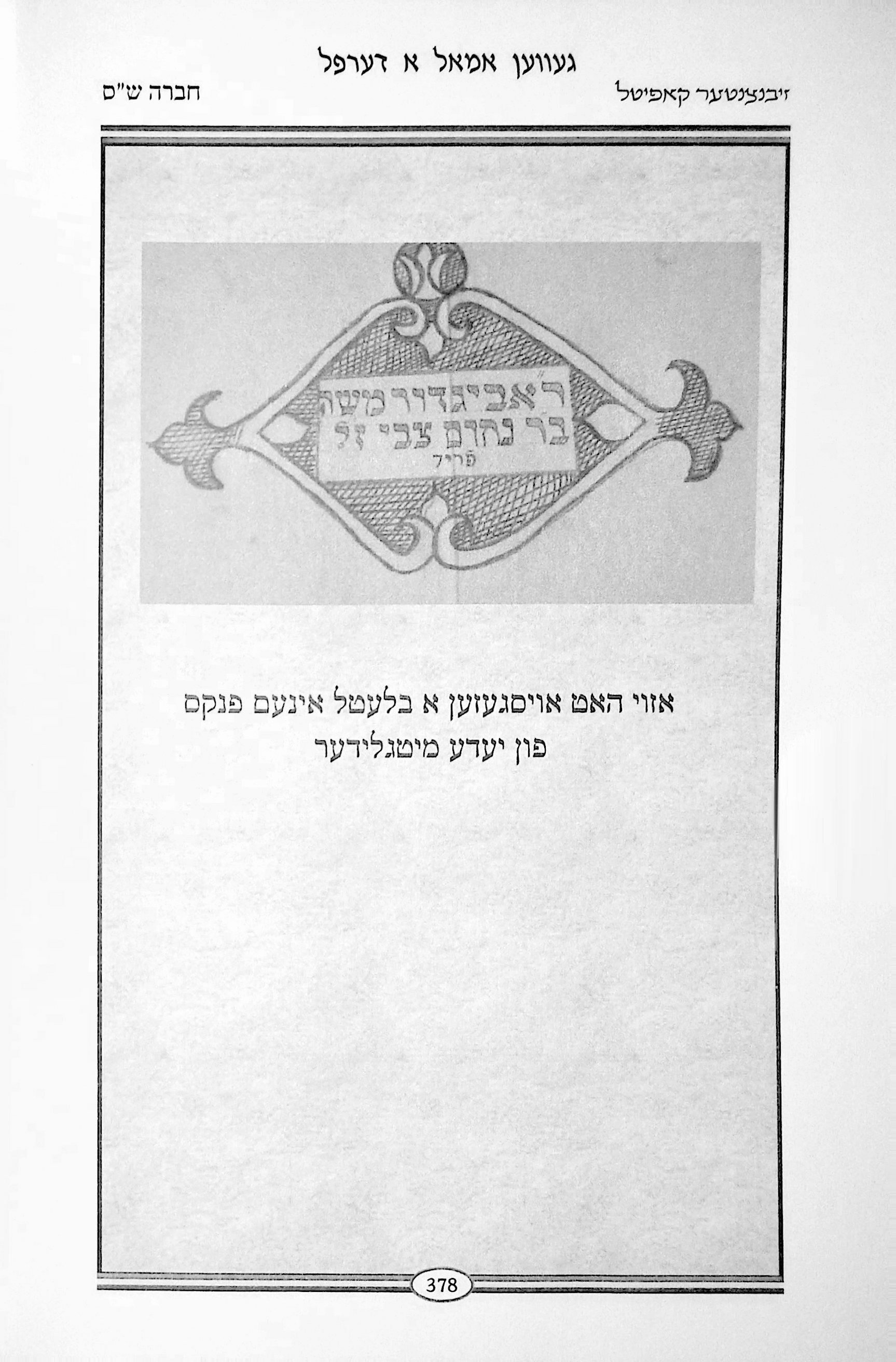

Zaidy Shlomo’s Father: R’ Avigdor Moshe ben R’ Nachum Tzvi.

- Born: 1861.

- Originally lived: in Borsa, and moved to Sacel.

- Spouses: Married to Etya Fried (daughter of his uncle, Yuda Fried) and later to the almanah Draizel Fruchter.

-

Yahrtzeit: 24 Av (Chaf Daled Av).

- Niftar: Wednesday, Parshas Re'eh, 5699 (August 9, 1939).

Vizhnitz Lineage Context

- The Baal Tzemach Tzadik: R’ Menachem Mendel Hager, youngest son of the Toras Chaim. He was R’ Avigdor Moshe’s first Rebbe and the founder of Vizhnitz Chassidus. Born in 1830; niftar October 18, 1884.

- The Vishiver Rav: (1886–1941). Mentioned below as having met R’ Avigdor Moshe in his home. He oversaw the affairs of Sichel when they did not have a Rav. He was the son of R’ Yisroel Hager, who was the son of R’ Baruch, who was the son of the Tzemach Tzadik.

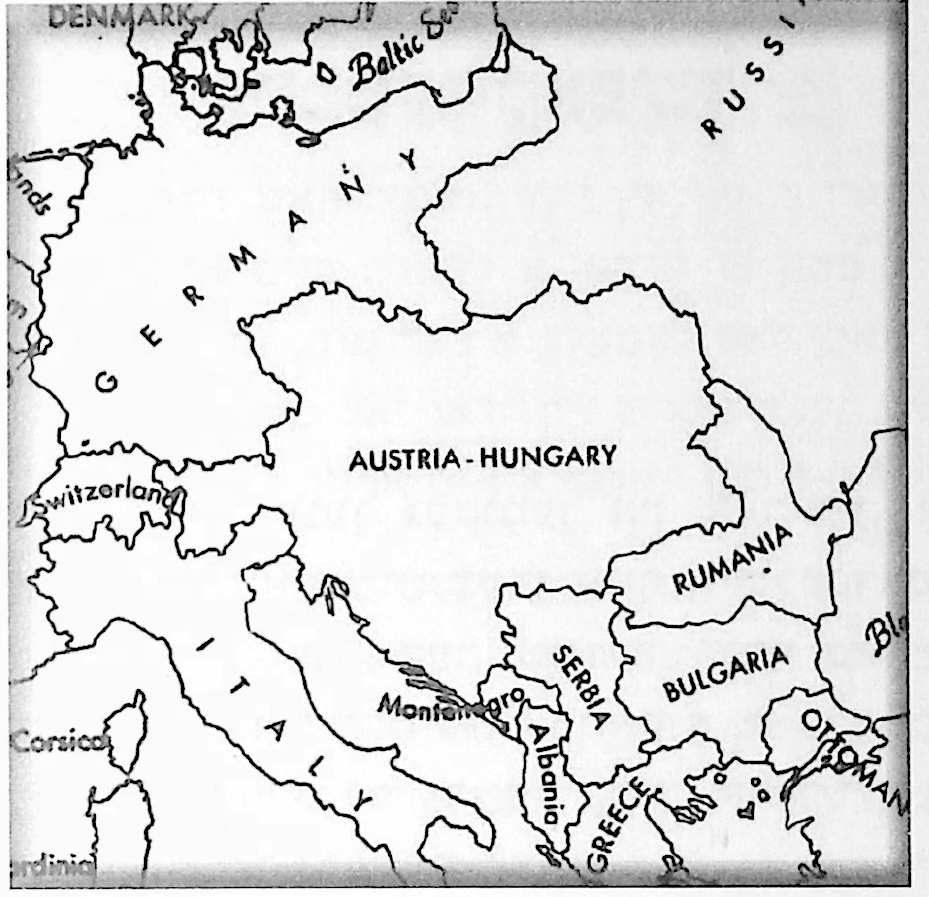

Historical Context: The World of Sichel

The Village of Săcel (Sichel)

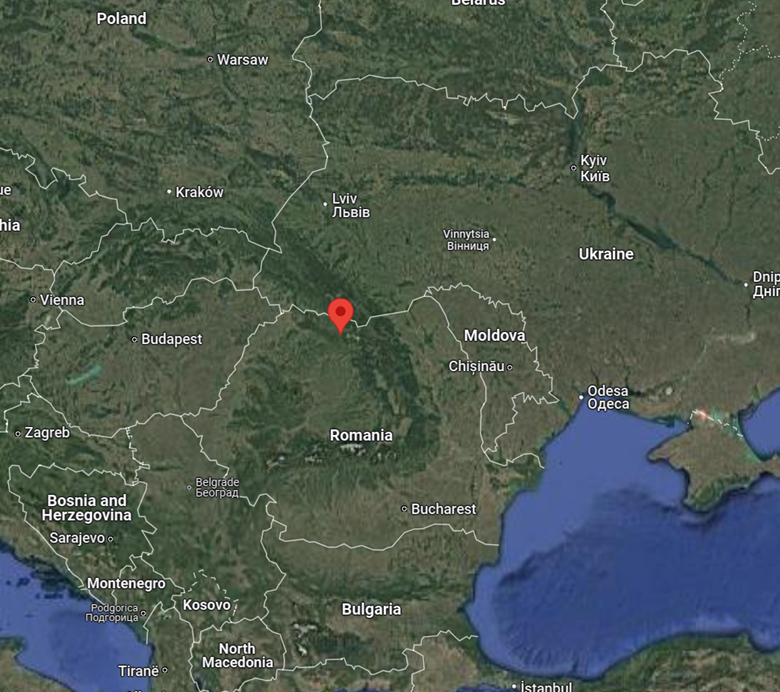

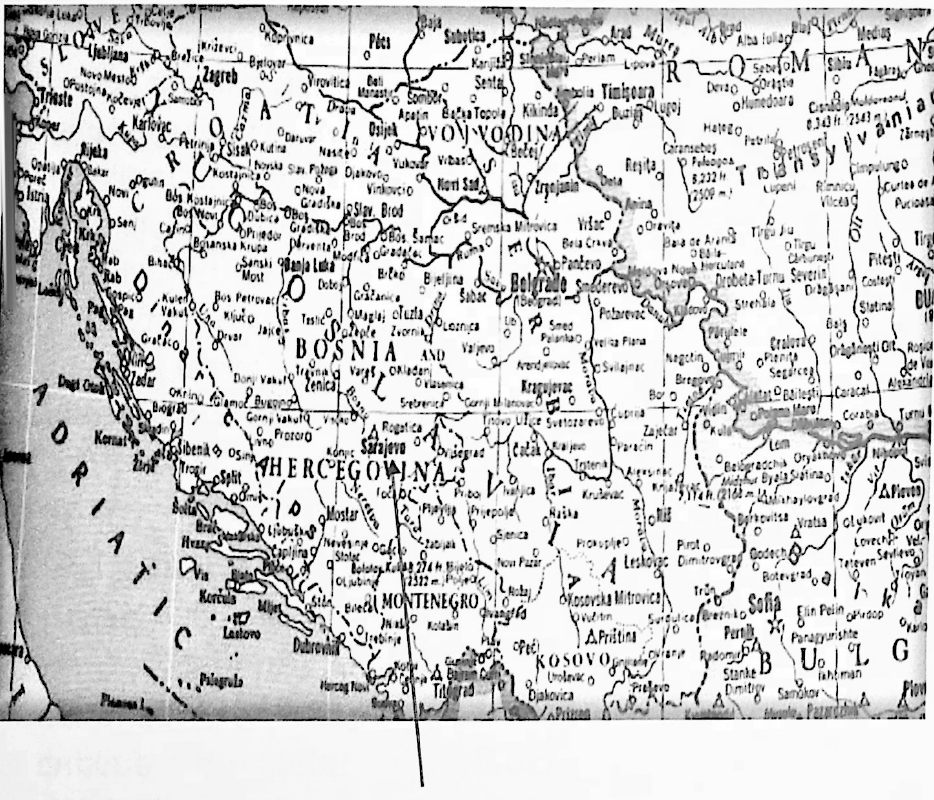

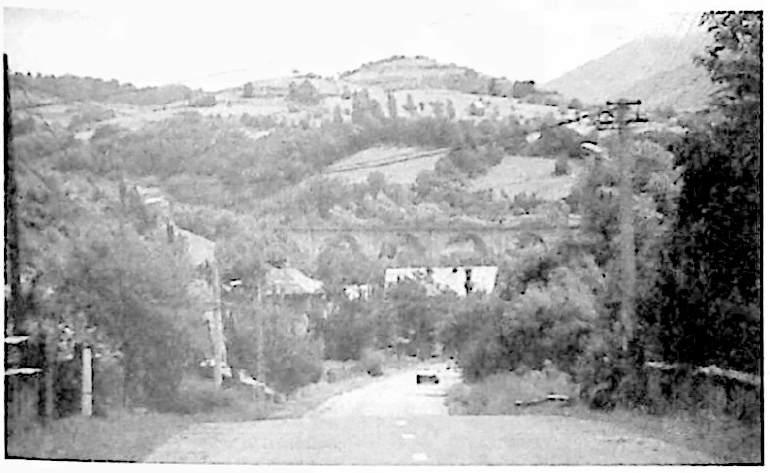

Săcel (known in Yiddish as Sichel) is located in the historic Maramureș region of northern Romania, nestled in the valley of the Iza River. Unlike the dense urban ghettos of Poland, Sichel was a rural mountain village.

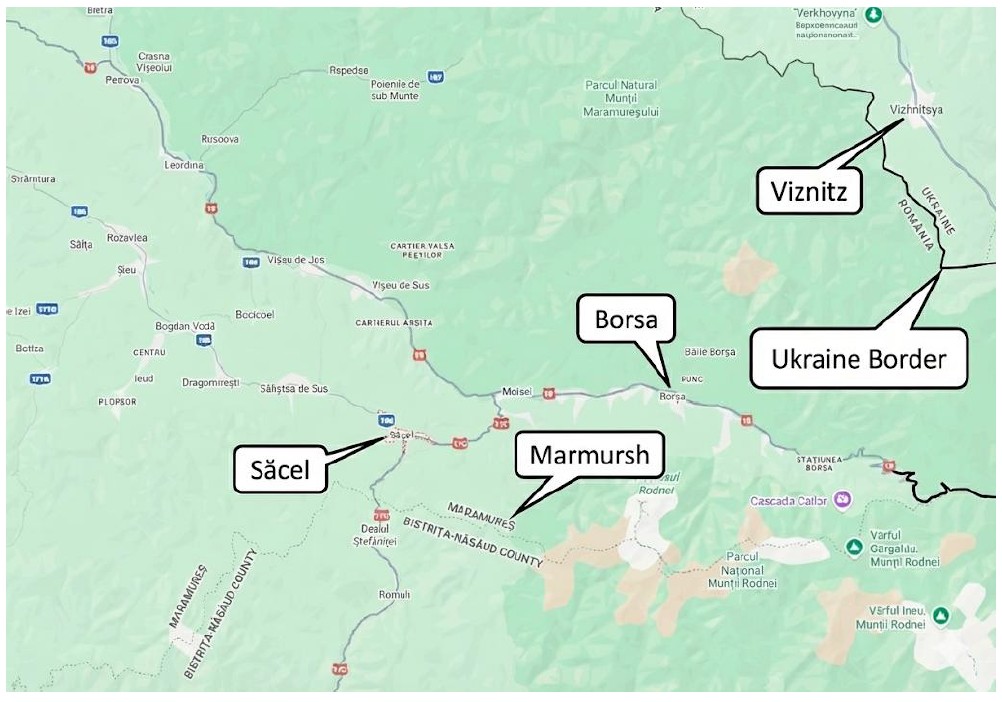

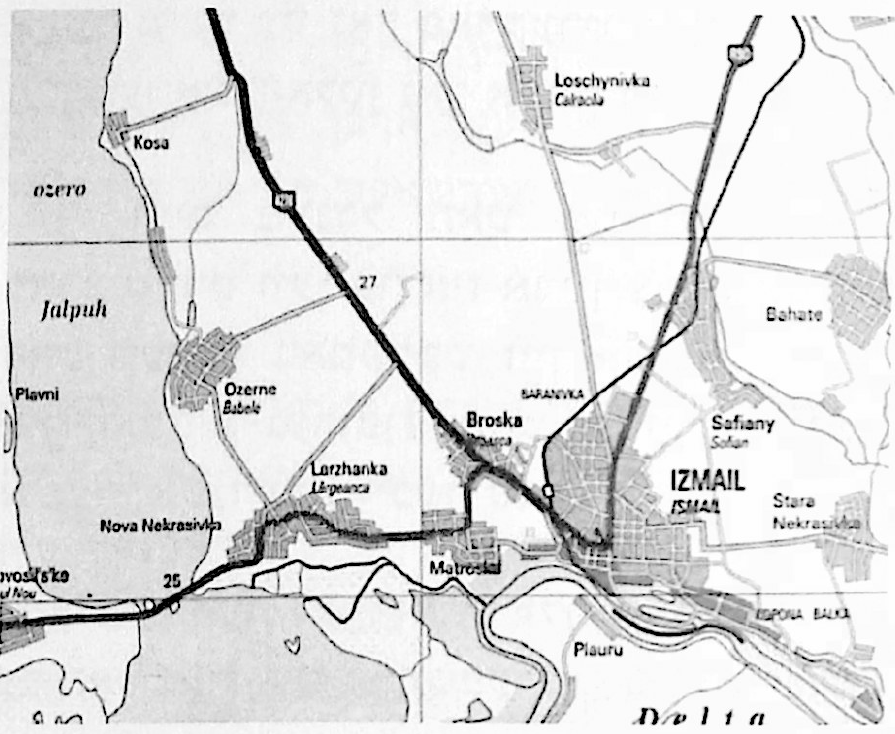

- Geography: It lies in a deep valley surrounded by the Carpathian Mountains, about 20 miles south of the Ukrainian border. It is approximately 90 miles (145 km) west of Vizhnitz which is in Ukraine. While this distance seems short today, traversing the rugged Carpathian mountain passes by wagon to visit the Rebbe was an arduous journey. The entire town is just 30 sq miles. You can use this Google Street View link to get a sense of it.

-

You can use this Google Street View link to get a sense of it.

View Sacel, Romania in Google Street View

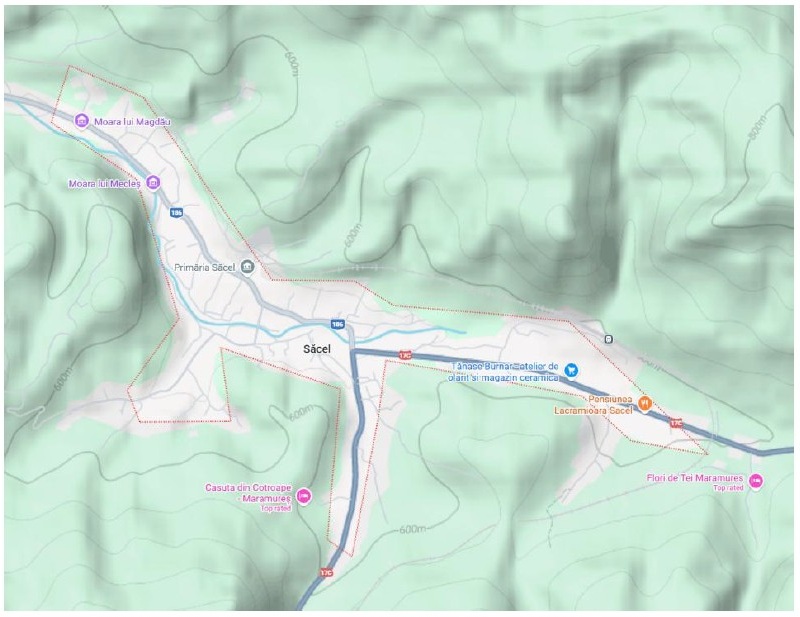

Figure 1 — Sacel. Note the mountains and the water.

Figure 2 — Notable places.

- Economy: The village was famous for its traditional unglazed red pottery (a Dacian craft unique to the area) and watermills powered by the Iza River. The soil was poor for farming, so most residents—Jews included—struggled to make a living.

Figure 3 — Sichel today.

Jewish Life in the "Derfel"

The Jewish community in Sichel was small but vibrant, deeply connected to the Chassidish communities of Vizhnitz and Sighet.

- Religious Authority: As a small village, Sichel did not always have its own official "Rav." Instead, it fell under the jurisdiction of the Vishiver Rav (R' Menachem Mendel Hager of Vizhnitz), who is mentioned in the family story as visiting R' Avigdor Moshe.

- Local Leadership: The "Dayan" mentioned in the story, R’ Yechezkel Weidman HY’D, is a historically documented figure. Records from Maramureș confirm that R' Yechezkel Weidman served as the local religious authority in Săcel and was known for his subservience to the Vishiver Rav—exactly as described in the family book.

The War Years

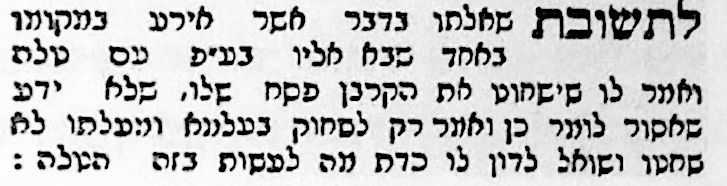

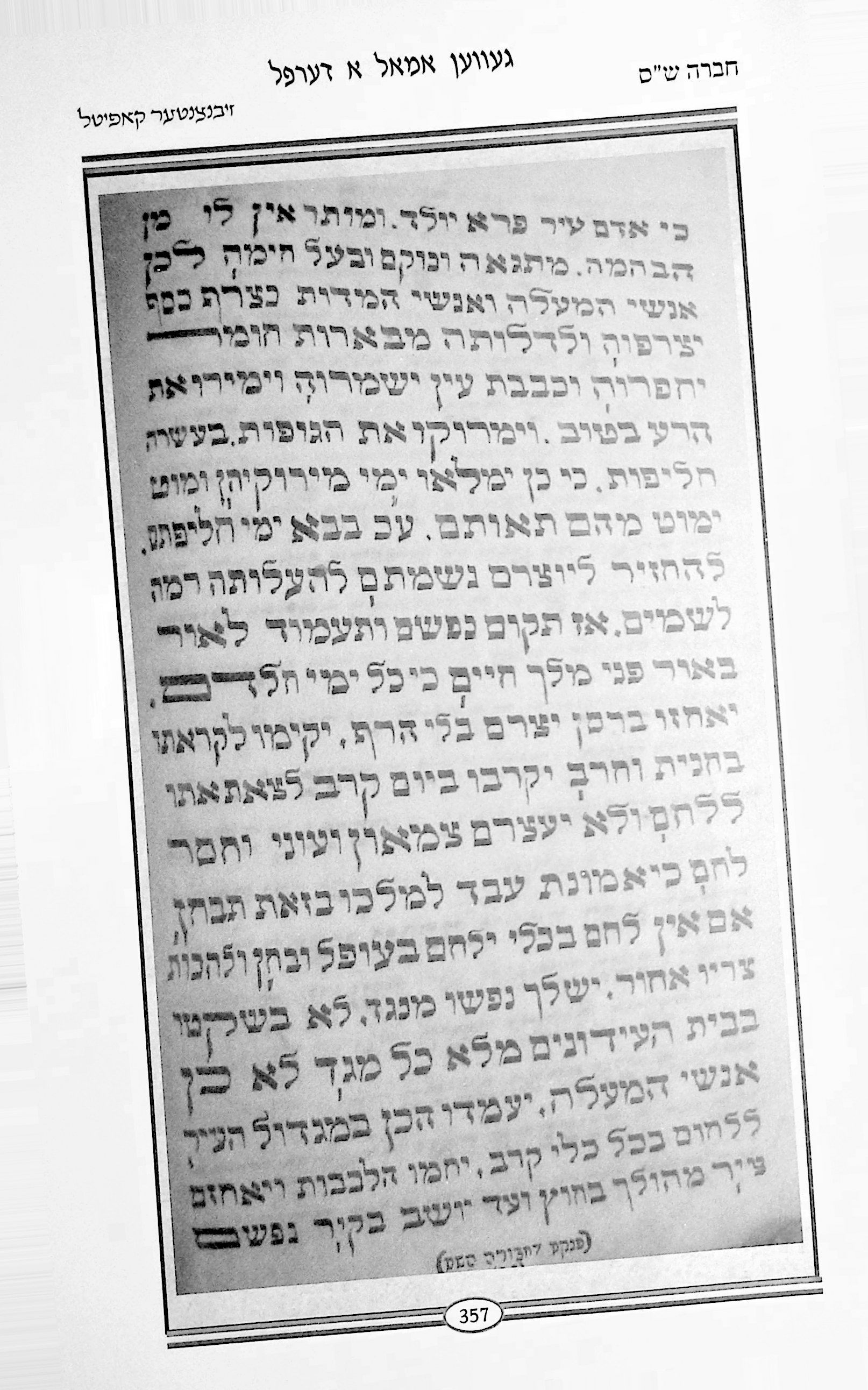

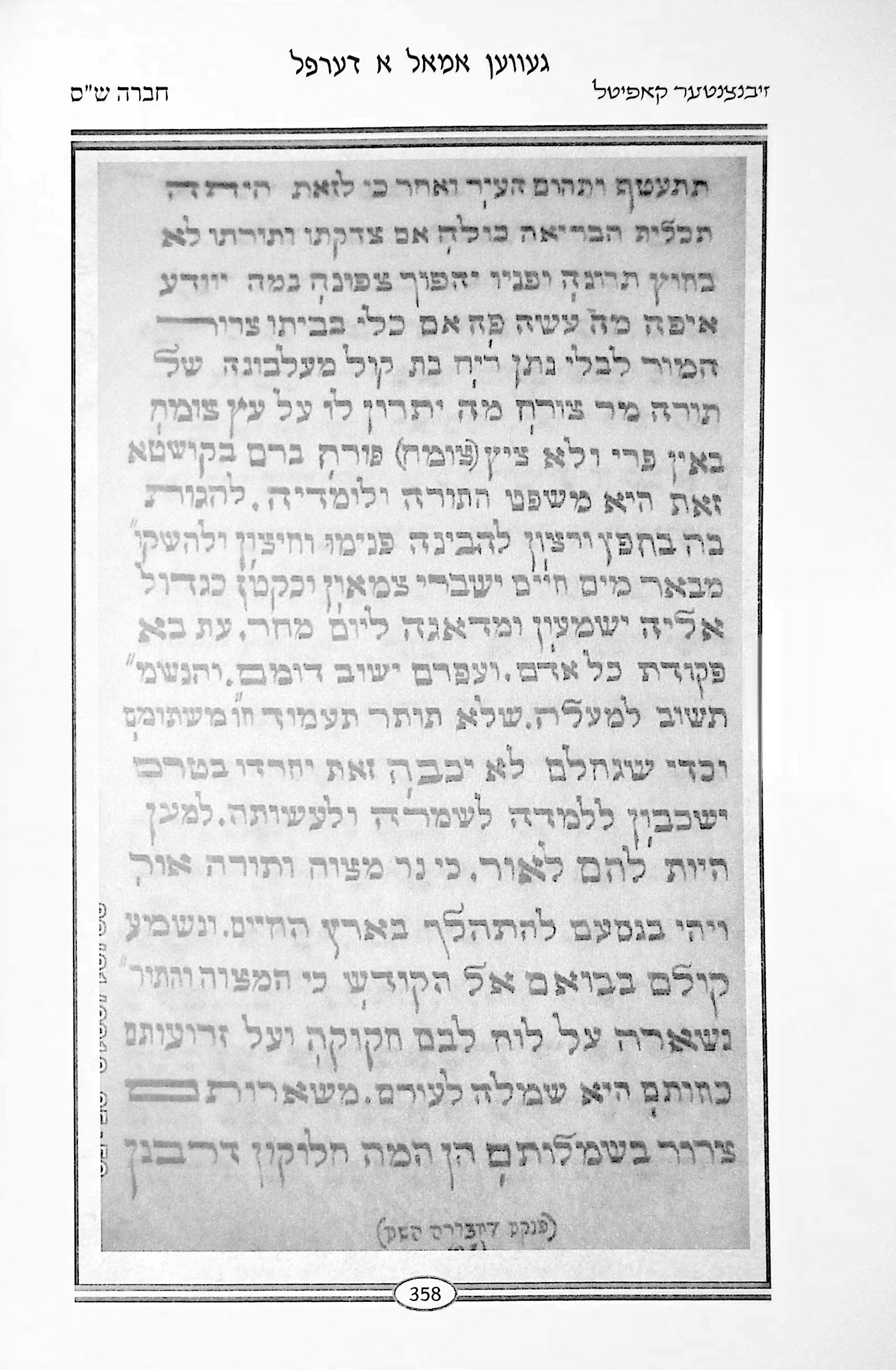

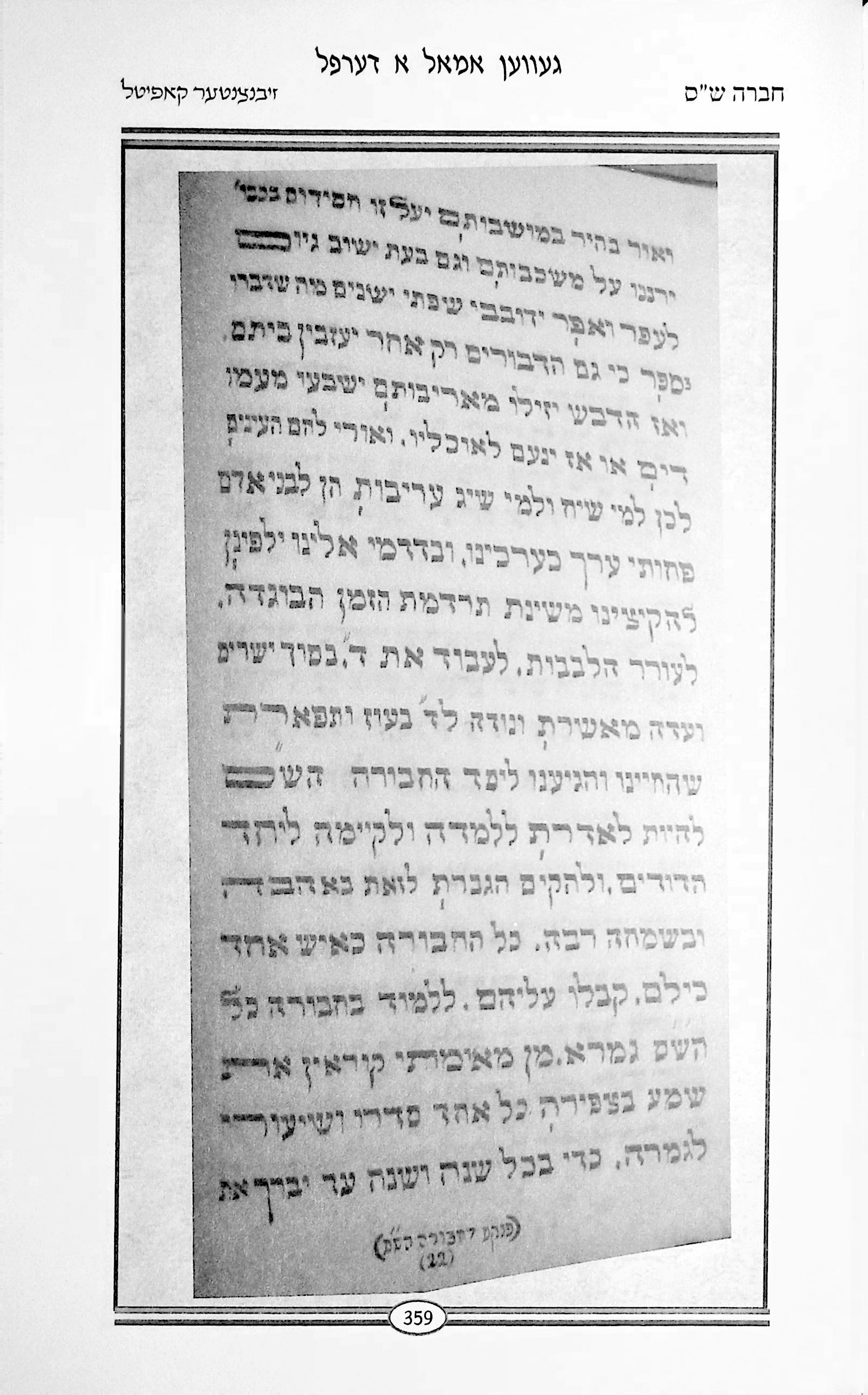

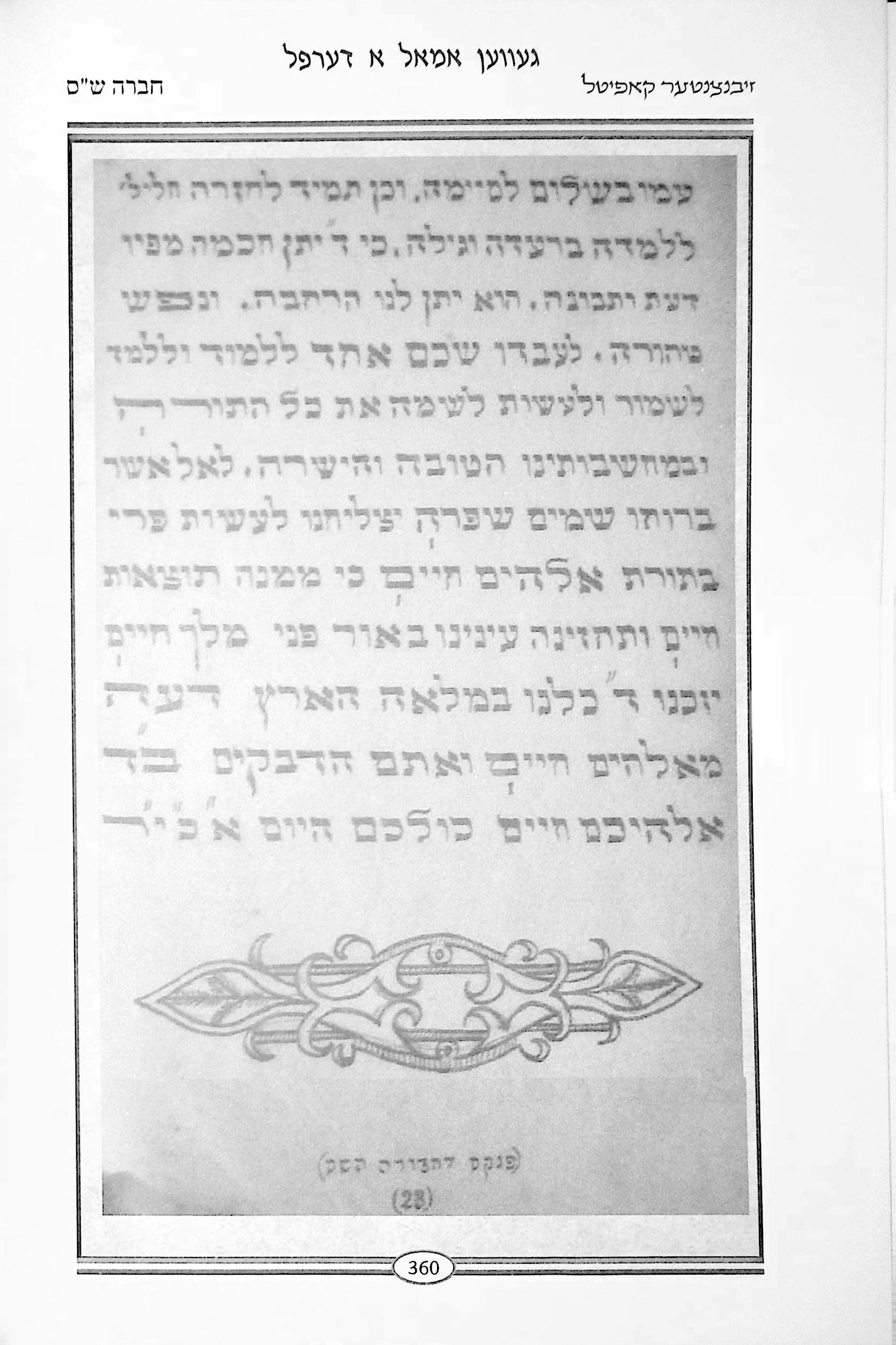

The peaceful life in Sichel ended abruptly. I remember hearing stories of how the ‘goyim took away our stuff’. It was much more than that. This text is a quote from the Chevra Shas diary:

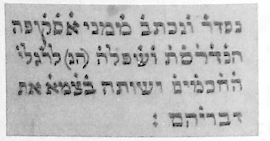

ולרוב עונינו ודאבון נפשינו נגרשנו ד׳ יתרו חדש הכל ופרט הכל מישובינו ע״י הרשעים שלנו , והקב״ה הצילנו מידם, כי תיכף בפרשת משפטים השגנו רשיון מאת שרי הממשלה לחזור כ״א לביתו. הודו לד׳ כי טוב כי לעולם חסדו – רשמתי למזכרת כי לא תמנו כי לא כלו רחמיו

- 1940 (Hungarian Occupation): The region was transferred from Romania to Hungary. Anti-Jewish laws were immediately enforced, and men were often drafted into forced labor battalions.

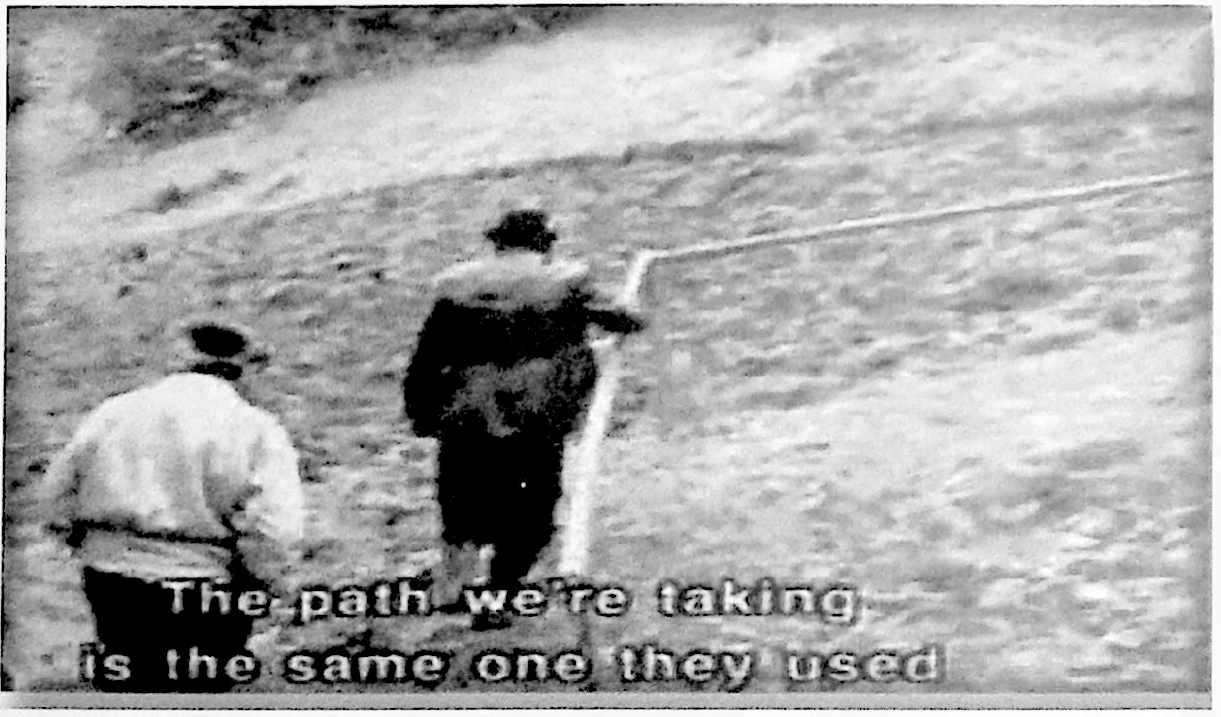

- 1944 (The End): The mention of Dragomirești in the story of the streimel below is also chillingly significant. In April 1944, after the German occupation of Hungary, the Jews of the Iza Valley (including Sichel) were rounded up and forced into a ghetto in Dragomirești (and later Sighet) before being deported to Auschwitz in May 1944.

- R' Avigdor Moshe's Fate: The story notes that R' Avigdor Moshe passed away in August 1939, just three weeks before WWII began. The text refers to him as being "gathered in before the evil," sparing him the horrors that befell his community a short time later.

Thanks for reading — Mordy Fried

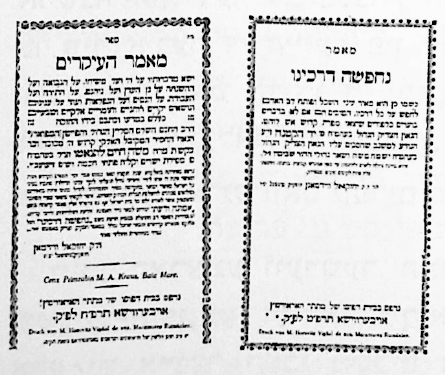

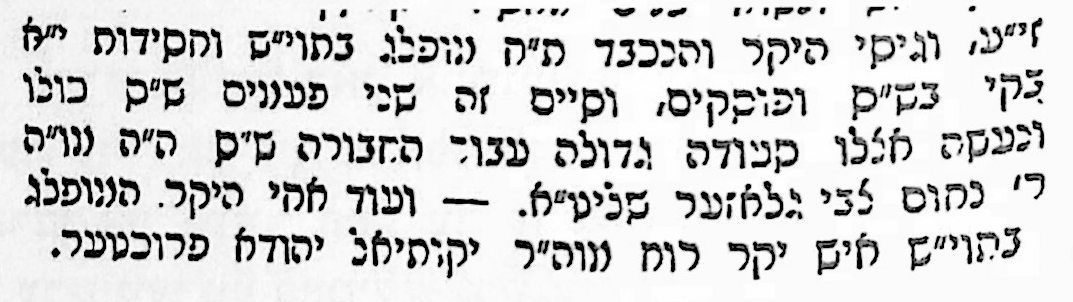

Publisher’s Foreword

Jewish history books, stories of Tzaddikim, and folktales from the אלטער היים revolve mainly around the great, central cities of Europe that held a prominent place in Jewish life. These were the cities that served as the bases for all material and spiritual matters, where ישיבות, חסיד'ישע courts, and famous קלויזן were established, from where the אור תורה was spread across the entire world and immortalized in ספרים—these cities have never been erased from the Jewish maps, and are constantly mentioned to later generations in descriptions of the beautiful past.

Traveling through the former Jewish lands of Europe, however, we also find signs of Jewish communities in remote, forgotten places. The position that these little towns, villages, and hamlets held for so many years has never been ascribed to their names, despite serving as a loving home for ערליך Jews and Jewesses, the forefathers of a significant part of today's כלל ישראל.

Although these settlements did not produce רבנים, אדמו"רים, or ראשי ישיבה that made the world tremble, the קול תורה filled their שטיבלעך with daily שיעורים, and in their חדרים and ישיבות קטנות, charming boys learned with a carefree desire. And although the vast majority of their inhabitants were burdened by the struggle for livelihood—על המחי' ועל הכלכלה—these worries did not touch their יראת שמים and תמימות, their אהבת התורה and התמדה according to their level, their התקשרות and אמונת צדיקים, their מדות טובות and מסירות נפש for אידישקייט. And yes, there were also great תלמידי חכמים among them, those who learned and knew, but their names remained within the walls of the בית המדרש.

Just such a settlement was our village, Sitchel. Its importance to the כלל is quite insignificant, and its history is far from famous. But it still has a history to tell us, the history of the Jewish inhabitants who breathed its air, walked its streets, lived in its little wooden houses, and viewed it as an integral part of their lives.

Our book, "Once Upon a Village" [געווען אמאל א דערפל], tells this story.

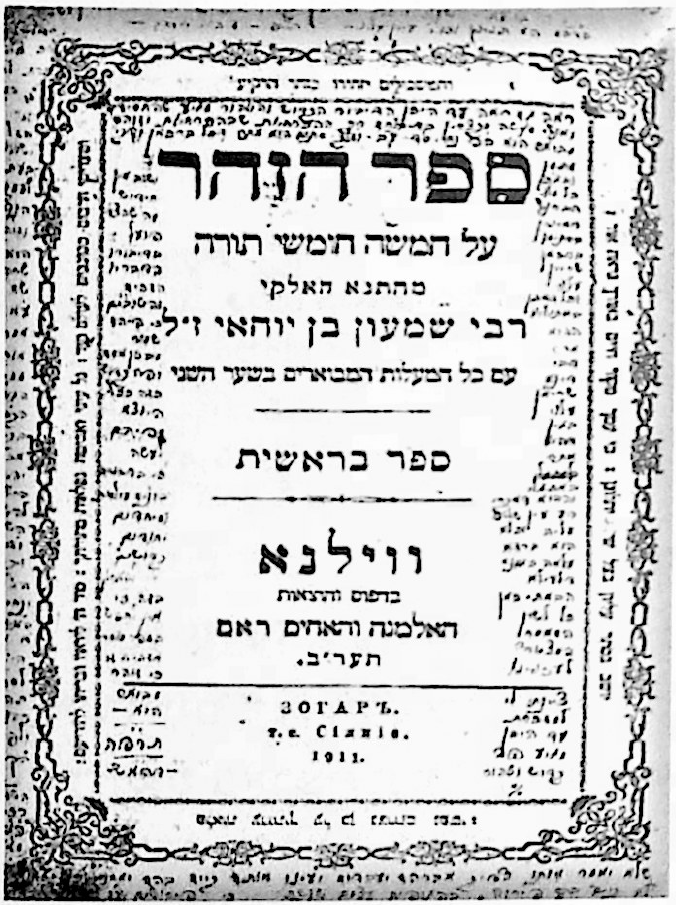

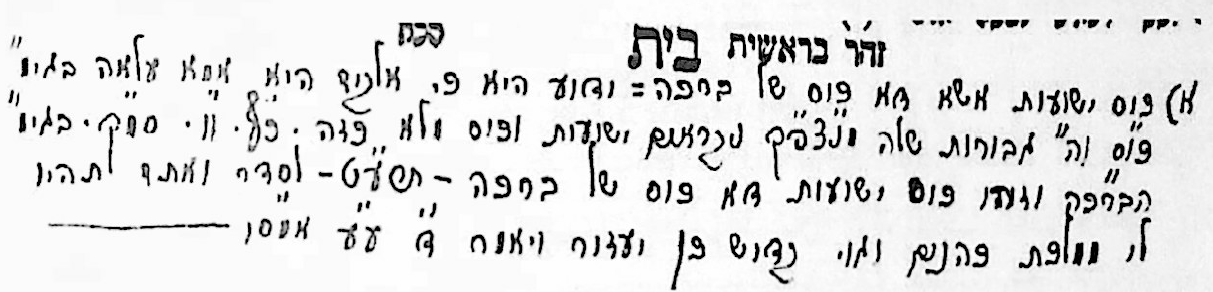

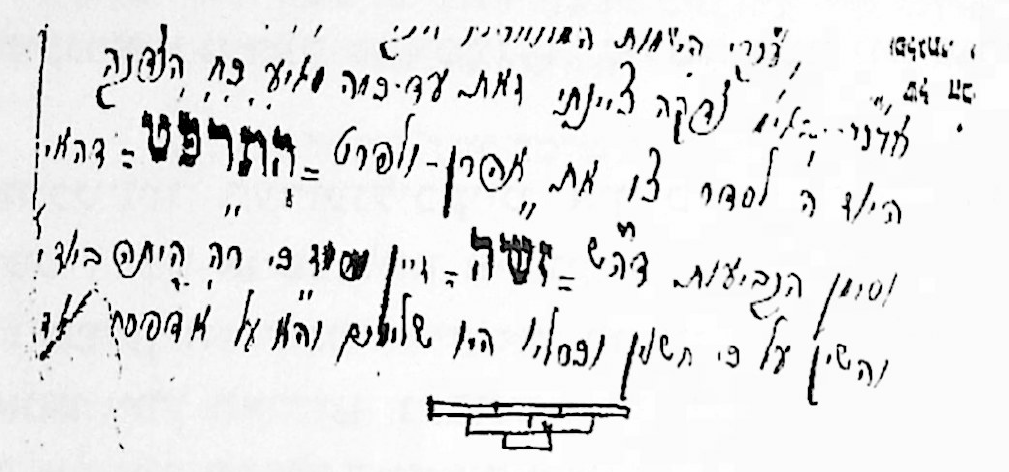

It tells of a slaughterhouse where the two butchers and the שוחט debated over the שחיטות — with a correct proficiency in הלכה from all sides; a wedding in the shtetl where the prize student of the ישיבה took a simple יתומה when the real חתן ran away; the ספר הזוהר that belonged to the large בית המדרש, inside of which one can still find the handwritten notes of R' Moshe Leib.

Our narrative portrays R' Avigdor Moshe Fried, whom the בחורים wanted to avoid so much that they preferred to learn at the Widow Landau's house—in a room she set aside for a שול—instead of in the large בית המדרש; Bluma Malik, who hired the village women to sew a carpet for the room where the Kossover Rebbe used to stay in her home; the modest R' Hersh Mendel Ganz, whose surprising death revealed the secret of his life.

Our history tells of the life and creativity of simple and not-so-simple shtetl Jews from a settlement in the Maramureș region of Romania. Get to know its inhabitants and types, live with its daily rhythm and its שבתים and ימים טובים, and learn about its bitter end and its condition today. May this book serve as a זכרון לטוב for every tiny, beautiful shtetl and village that once served as an עיר ואם בישראל, and is therefore worthy of being remembered for its quiet but vital role in the existence of כלל ישראל.

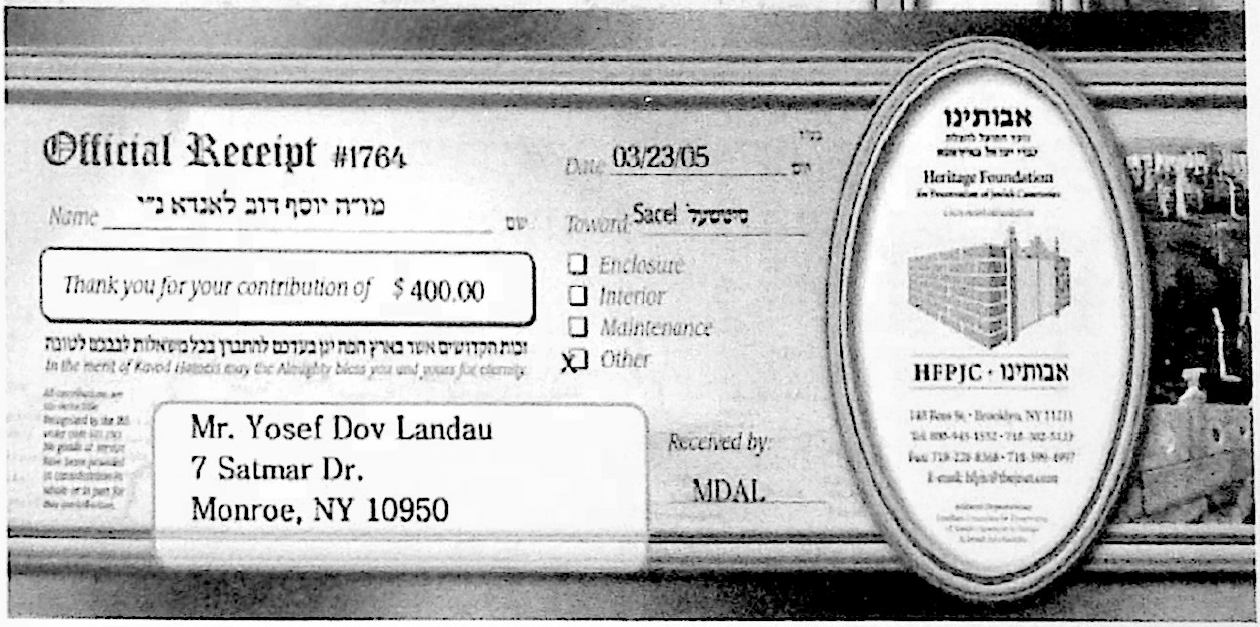

Yosef Dov Landau

מוציא לאור

There Was Once a Village

Sitchel In Happiness

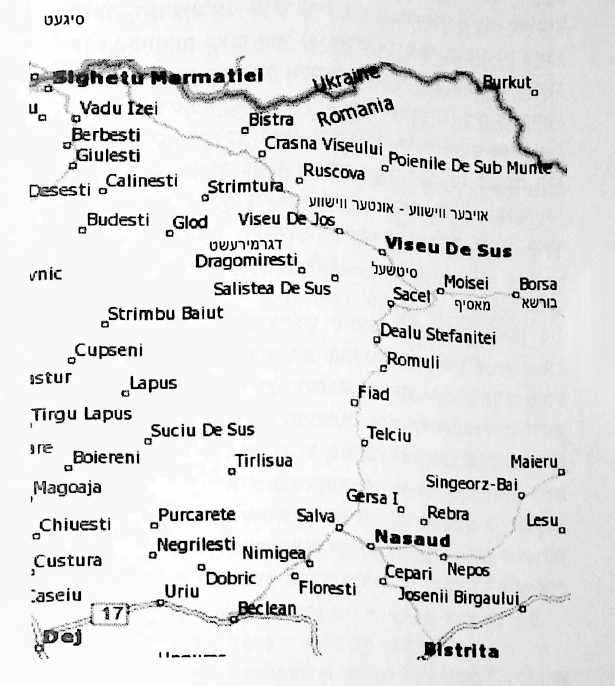

Early Sacel Map, Find important places in Yiddish top 3rd.

Sacel Present Day (2026) - Note Vinnytsia (Vishnitz)

Chapter One — A Glimpse into the Village

A Glimpse into the Village

Entrance to the village coming from Sighet

In a corner of Romania, where the Maramureș region borders Transylvania, stands a small, modest village.

Geography: The Mountain Fortress

Maramureș is famously isolated. It is surrounded by the Carpathian Mountains, which acted like a natural wall. This geography kept the modern world out for a long time, allowing the Jewish community here to keep their traditions pure and unchanged, unlike in the big cities like Budapest where life was becoming more modern.

AI GeneratedThe name "Sitchel" itself implies nothing extraordinary, which is fitting, for its Jewish inhabitants were much like the village itself—quiet and modest, יראים ושלמים (God-fearing and wholesome). Even the local תלמידי חכמים conducted themselves with the restrained style of הצנע לכת (walking humbly), never seeking to immortalize their names with world-famous achievements.

Sitchel's neighbors are also largely obscure. To the east lies the village of Masif, perhaps better known today for the great תלמידי חכמים and authors of ספרים who emerged from there. To the west, about nine kilometers away, is the first village, Salisht. Then comes Dragmirest, a town travelers had to pass through on the way to Sighet. Strimba is the closest neighbor to the south, sitting just outside the Maramureș border as the first village leading into Transylvania.

Geography: The "Yiddish Map"

Jews and Romanians lived in the same space but used different maps. Masif is the Yiddish name for Moisei (site of a tragic massacre in 1944). Salisht is Săliștea de Sus. Strimba is Strâmbu. The Jews created their own version of the geography, using Yiddish names instead of the official Romanian ones.

AI Generated

The Iza River

Sitchel and its Joys

The name "Sitchel" is derived from the Romanian word *sat*—meaning a settlement. The suffix *chel* acts as a diminutive indicating its small size, much like our Yiddish *le*. (The city of Satmar implies the reverse—the suffix *mare* means "big," indicating a larger settlement).

Linguistics: Name Games

It is interesting that the two most famous names in this region—Satmar ("Big Village") and Sighet ("Island")—became the names of massive Chassidic dynasties, while "Little" Sitchel remained a quiet, humble town, exactly as its name predicted.

AI GeneratedThe village actually began on a very small scale. The entire area was once a dense, wild forest of trees and tall grass. Gradually, the populations of nearby villages began to expand their borders toward the Iza River, which skirted one side of the woods. The pioneers who first settled there were known as the "Print" inhabitants.

History: The "Print" Family

The term "Print" is likely a Yiddish pronunciation of Perényi. The Barons of Perényi were a powerful Hungarian noble family who owned huge amounts of land in this region for centuries. The first inhabitants were likely tenant farmers working on the Baron's estate.

AI GeneratedThese villagers found the forest to be an excellent source of livelihood. A sawmill was established nearby where the locals brought the trees they had chopped down to be cut and processed.

The main street in Sitchel today

Under the hands of diligent workers, tree after tree fell, and the forest grew increasingly sparse. In the clearing where the trees once stood, an empty path took shape, eventually becoming the main street of the future village.

The region was especially blessed with the Iza River, which flows through Sitchel on the final leg of its journey through Maramureș. The Tisa River flows through Maramureș until just before Sighet, where it splits—one stream runs through the Vishevas, while the second flows through Sitchel toward Transylvania.

In those years, a local river was a major draw for potential settlers. Aside from providing water for daily household needs—laundry, dishes, cooking, and the like—it enabled the establishment of a local watermill. The river's current turned a massive wooden wheel, driving the internal millstone to grind wheat kernels into flour.

Current Event: The Mill Still Stands!

Fascinatingly, this watermill still exists today! It is known as Moara lui Mecleș (Mecleș Mill). Built around 1907, it is still powered by the Iza River. It doesn't just grind flour; it also has a water-powered wool processing machine used to make the heavy rugs characteristic of the region. It is now a popular tourist attraction.

AI Generated

With its numerous natural advantages, the cleared ground began to attract people in greater numbers. To create living quarters, the newcomers built rows of houses, one close to the next. As more people arrived, fresh trees were felled to make room for more homes, and the village of Sitchel was officially founded.

The Jewish Population

Jewish history in Sitchel spans about 150 years. As the settlement began to form, the prospect of work attracted Jewish laborers. A small number of Jews participated in the initial construction of Sitchel, and others gradually followed. At first, the Jewish community made up 7% of the population, but that number steadily rose, peaking at 12%. In the years before the war, 140 of the 650 families who called the village home were Jewish, comprising a קהילה of 700 souls.

The arrival of the Jews introduced a new standard of living to Sitchel. Until then, the villagers had lived in wooden peasant huts; the Jews, however, having lived in the more advanced environment of Western Europe, erected houses with sturdier architecture. After the Jewish community was established, new peasant houses began to follow this improved style as well.

Architecture: Wooden Wonders

Maramureș is famous for its "All Wooden Buildings"—tall, spiky buildings made entirely of wood without nails. The Jews adopted this local style, building beautiful wooden Synagogues. Sadly, because they were wood, they were easily burned down during the war. Today, Săcel is also famous for Red Unpolished Pottery, an ancient Dacian craft that local Jews would have traded.

AI GeneratedThe Jewish homes stood on stone foundations, with a cellar beneath every dwelling to store food throughout the winter. The apartments were built of durable materials like brick, iron, and stone, featuring brick chimneys and wide windows with shutters that could be opened or closed for comfort.

Survival: The "Root Cellar"

The cellar was not a storage closet; it was a life-support system. In winters that hit -4°F, the earth insulated the cellar, keeping it just above freezing. This stopped potatoes from freezing (which turns them to mush) and stopped apples from rotting. If your cellar failed, your family starved.

AI GeneratedThe 140 families of the Jewish community were extremely close-knit, regarding themselves as one large, warm family. While the majority of residents were indeed related, even those not connected by marriage were beloved friends with everyone, living together like brothers.

This brotherhood among the Jewish residents evoked deep respect from their non-Jewish neighbors, who also adapted to the cooperative village atmosphere. The unity extended to the gentile quarters, fostering a peaceful and pleasant environment for all of Sitchel's residents. Both segments of the population relied on one another, and quarrels between neighbors were rare.

With their natural head for commerce, the Jews brought various goods into the village to sell to the local farmers, benefiting both sides. Utilizing their frequent travels across Eastern Europe, the Jews introduced the backward farmers to advanced products developed in other regions.

For example, the Jews introduced paraffin, a lighting fuel much cheaper than the wax used previously. They provided glass for windows, goose-down bedding instead of straw, metal pots instead of earthenware, and iron chains instead of tied ropes. Jewish neighbors also sold them necessities such as nails, fabric, cooking utensils, spades, and many other household goods.

Technology: The Paraffin Revolution

Paraffin (Kerosene) changed everything. Before this, peasants went to sleep when the sun went down because wax candles were too expensive. Cheap kerosene lamps extended the day, allowing Jews to study Torah late at night and allowing business to happen after dark.

AI GeneratedHealth: Metal vs. Clay

Replacing earthenware (clay pots) with metal pots was a huge health upgrade. Clay is porous and absorbs bacteria and grease, making it hard to keep clean and hard to keep Kosher. Metal could be scrubbed and boiled, improving hygiene for the whole village.

AI GeneratedCulture: The "Feather Plucking"

The text mentions "goose-down bedding." Plucking these feathers (Schleissen) was a major winter activity. Women would gather in a house, tell stories, and strip the soft down from the quills to make the heavy duvets needed for the freezing winters.

AI GeneratedDr. Petrescu, a Sitchel native who is now a medical doctor, depicts his former Jewish neighbors in a highly positive light in his memoirs. He writes:

"Their [the Jews'] behavior within the Romanian population was always polite and impartial. I do not remember any quarrels, arguments, or legal complaints regarding immoral acts, abuses, or thefts in which a Jew was involved. [This is] because they kept the laws of decency implanted in them from earliest youth by their parents, thanks to the morality ingrained in the entire Jewish community through their religious obligation. This conduct led to a peaceful social interaction with the Romanians, based on respect and mutual support."

History: The Rare Memoir

It is very rare to find written records from the non-Jewish neighbors. Most peasants were illiterate. Dr. Petrescu's memoirs are a valuable historical document because they confirm from an "outsider's" perspective that the Jewish community really was as honest and peaceful as they claimed to be.

AI GeneratedHowever, the polite behavior of the Jews toward the gentile villagers did not compromise their רוחניות (spirituality) by a hair's breadth. Every single Jewish inhabitant ran an honest and God-fearing home, never deviating from the מסורה (tradition) by so much as an iota.

Their mode of dress was authentically חסיד'יש—long קאַפּאָטעס, שטריימלעך, and faces framed by beards and curled פאות. The thought of feeling embarrassed before their gentile neighbors never even crossed their minds. In the surrounding villages, "the Iza inhabitants"—as the Sitchel Jews were known—were famous as extraordinary יראי שמים, serving the Al-mighty with the highest level of piety and caution.

Parnassah (Livelihood)

For a time, the village was blessed with a respectable source of income that brought a flow of plenty and wealth to its inhabitants. At the edge of the village, a gushing oil spring was discovered—a highly marketable resource used as fuel for trains.

To harvest this valuable fuel, a massive, powerful oil pump was erected on the site. A large number of locals busied themselves extracting the underground treasure and delivering it to numerous clients in the surrounding regions, providing פרנסה (livelihood) with a generous hand to all involved in the production.

History: The Oil Boom

In the late 1800s, Romania had a massive "Black Gold" rush, becoming one of the world's biggest oil producers. Săcel sits on a real oil field (still known as the Săcel Oil Field). The book's description of a boom town matches historical records of the time when oil rigs suddenly popped up in cornfields.

AI GeneratedDemand for the merchandise grew stronger, and requests for larger quantities of oil poured in from all sides. Skilled workers labored ceaselessly at the pump to fill orders on time, ensuring buyers left satisfied and would return to the Sitchel oil factory for future purchases.

The booming success of the business placed the Jews in a difficult נסיון (test), and unfortunately, some did not have the spiritual strength to withstand it. In an attempt to speed up production for the growing customer base, work at the pump was extended to seven days a week. Tragically, several Jews in honest Sitchel stumbled weekly in חילול שבת רח"ל (desecration of Shabbos, Heaven forbid).

Since Sitchel did not have its own Rav at the time, there was no one to stand up and object. The terrible sin was committed בפרהסיה (publicly) on a regular basis, and no one dared to make an issue of it.

From time to time, distinguished Jews and Rabbonim would visit Sitchel for Shabbos, just as they did other towns. When one visiting Rav encountered this heaven-crying injustice on the holy day, he was shaken to the core: *Heimishe* Jews, whose parents had practiced מסירות נפש (self-sacrifice) to keep Shabbos properly, were being sold for money, ready to desecrate the day of rest for a few cents!

The incident shook him so deeply that he could not hold back a curse. "May the oil spring dry up," he cried out, trembling, "and may it cease springing forth tests for Jews!"

Not long after, the flowing oil stream suddenly died. The spring from which so many drew their livelihood was gone, and with it, the era of plenty in Sitchel came to an end. Only the massive pump remains to this day as an eternal memorial.

The massive oil pump station

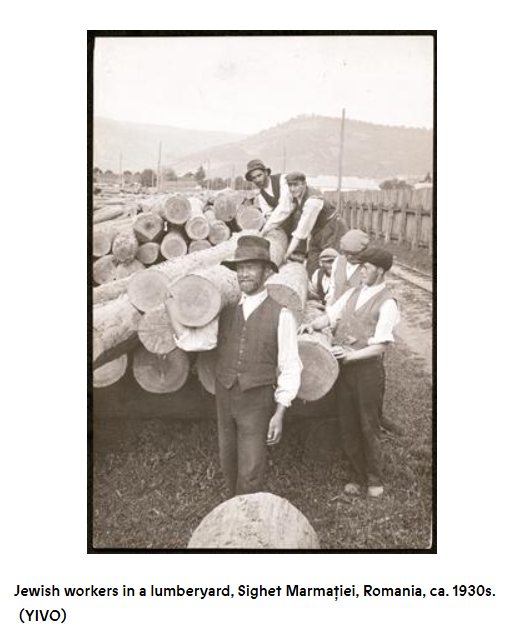

Sitchel had its share of wealthy men who utilized the surrounding forests for business. Some merchants, like R' Yisroel Leib Stegman, worked in the timber industry. R' Yisroel Leib established a lumber factory near Sitchel, on the highway leading to Nasaud, Bistritz.

Hundreds of workers—Jewish and להבדיל gentile—were employed by his company. First came the lumberjacks, who felled trees in the section of forest he had purchased. Then his porters transported the logs to the factory, where other workers piled them up, ready for the advanced steam-sawmill.

Technology: Steam Power

The text mentions an "advanced steam-sawmill." This was a big deal. Older mills used water wheels (which froze in winter or slowed in summer). A steam engine could run 24/7, regardless of the weather, allowing for mass production of lumber on a scale never seen before.

AI GeneratedOnce the sawmill was fired up and the logs inserted, a wood-pusher guided the timber toward a series of saws that cut it into boards of various measurements. Finally, other porters drove wagons filled with boards to the train stations for delivery.

Geography: The Strategic Railway

The text mentions delivering boards to the train. This refers to the strategic Salva-Vișeu railway line. This line runs through Săcel and was critical for connecting Transylvania to Maramureș. Later, during WWII and the Communist era, this same rail line was expanded using forced labor, a dark chapter in the region's history.

AI GeneratedThe sawmill employees worked in three shifts throughout the day and early night. Every workday, the factory siren sounded three times—at 6:00 AM, 12:00 PM, and 6:00 PM—signaling the workers to orient themselves and report for duty.

Culture: The Village Clock

In a village without electricity or public clocks, the Jewish sawmill's siren became the "Timekeeper" for everyone. The "Shabbos Siren" (stopping work on Friday) effectively started the weekend for the entire village, Jews and Gentiles alike.

AI GeneratedThe workers received a weekly wage. R' Yisroel Leib was very beloved by the villagers for the numerous jobs he created. He earned the complete trust of the Romanians just as he did להבדיל the Jews, carrying a *shem tov* (good name) as a capable, honest *baal habayis*.

Other forest merchants included R' Yitzchok Menachem Pollack, whose sawmill ran on power from the Iza River. R' Yankel's sawmill used the same system, stationed down on the Iza at the edge of the village. R' Yankel also owned a watermill for grinding wheat, as did several other Jews.

Other village Jews, like the brothers R' Yechiel Michel and R' Avraham Gross, utilized the surrounding mountainous fields for cattle trading. In the spring, they bought livestock and sheared wool from local farmers. Regarding this trade, Dr. Petrescu writes: "The Jews... paid on the spot... offering good prices."

History: The Shepherd Jew

In most of Europe (like Russia or Poland), Jews were forbidden from owning land or farming. But in these rugged mountains, the rules were loose. This created a rare type of person: the Farming Chassid. Jews in Sitchel weren't just merchants; they were active shepherds and dairy farmers, something almost impossible for Jews elsewhere.

AI GeneratedThese merchants rented meadows on the surrounding mountains and hired shepherds to graze the cattle throughout the summer. After three or four months, the cattle were fat and well-fed, ready for the market.

Some Jews established smaller enterprises. "Yudl's Horses" owned a pair of healthy, strong horses that pulled a large, tarp-covered wagon. R' Yudl made a living traveling to wholesalers and bringing back merchandise to stock the village shops.

Logistics: The "Trucker"

R' Yudl wasn't just a driver; he was the village's lifeline. Before paved roads or delivery trucks, a strong team of horses was the only way to get goods like sugar, kerosene, or cloth into the village. His wagon was the "Amazon Prime" of 1920s Romania.

AI GeneratedAnother Jewish resident bought a machine to produce ice cream for sale, while R' Dovid Werzberger purchased equipment to make soda water, setting up his shop in the center of the village on the main street.

Culture: The "Gazoz" (Soda)

The text mentions a soda machine. This refers to the classic "Gazoz" kiosk. By bringing carbonated water to the village, Jewish merchants were introducing a major "city luxury" to the peasants. In a world without soda bottles, getting a fresh, fizzy drink was a marvel.

AI GeneratedTechnology: Ice Harvesting

How did they make ice cream without electricity? In the winter, men would cut huge blocks of ice from the frozen river and bury them in deep pits lined with straw. This insulation kept the ice frozen well into the summer, allowing them to make ice cream in July using "harvested winter cold."

AI GeneratedA significant portion of the Jewish population consisted of simple tradesmen and shopkeepers. R' Kalman Fishman, for example, bought huge quantities of fruit—especially apples—every autumn. Throughout the long winter, the merchandise lay in his cellar (and in the cellars of obliging neighbors). Come spring, he dragged the fruit out of hiding and sold it for a good price.

Economics: Futures Trading

R' Kalman was essentially a commodities trader. By buying apples when they were cheap (harvest time) and storing them until they were rare (late winter), he created value. But it was risky—if the cellar got too cold, the apples froze; if too warm, they rotted. His profit depended entirely on the quality of his cellar.

AI GeneratedSome Jews worked hard and bitterly in the factories, earning barely enough to survive. There were those who traveled to the factory every Monday morning, remaining separated from their families until Friday afternoon.

Others, however, did not even have that. Sitchel had its desperately poor who sometimes lacked the means to put bread on the table. It was not uncommon for a Jew to fold his טלית ותפילין in the morning without the slightest clue where he would find a stitch of work that day.

Sociology: The "Luftmensch"

The text describes a Jew with no clue where work would come from. This is the classic archetype of the Luftmensch ("Man of Air")—someone who lived on wit, miracles, and odd jobs. It highlights the big gap between the rich and poor in the shtetl: for every timber baron, there were dozens of families living on faith.

AI GeneratedThe wealthier Jews in the village were always ready to help their needy neighbors. In the brotherly atmosphere that reigned in Sitchel, everyone knew everyone's business; when it became known that someone was struggling, kindhearted Jews lent a shoulder.

On Wednesday afternoons, money was collected from Jewish homes so the poor of the village would have enough to prepare for Shabbos. The צדקה was given as מתן בסתר (anonymous charity) to protect the dignity of the needy. With the generous support of their Jewish brothers—and a rock-solid בטחון in the One who is זן ומפרנס לכל (sustains and supports all)—the poor overcame their tight times with strength and inner contentment.

Social Safety Net

The "Wednesday Collection" was a standard Jewish system. Collecting on Wednesday ensured the poor had money by Thursday morning, allowing them to shop for fish and meat at the market *before* the prices went up or the good food was sold out. It protected their dignity by letting them shop like everyone else.

AI GeneratedChapter Two — The Daily Routine

The Daily Routine

Long before the glow of electric lights reached the remote villages or automobile wheels turned over their unpaved streets, Jews called Maramureș home. Modern luxuries hadn't appeared even in their wildest dreams; the simple village Jews had humbler hopes—that the chicken would return kosher from the שוחט and that the cracks in the walls would keep out the cruel winds. Their aspirations were small and their standards simple; only in this way could the peaceful village life continue with such minimal comforts.

The early pre-dawn hours found the village woman standing by the oven, feeding it wood to warm the freezing house. Thick logs wouldn't catch fire from a simple match; to get the fire going, she had to spread *shpendlech*—thin wood shavings and sawdust that caught fire easily—over the wood and light them. To ensure the flames spread to the logs before the *shpendlech* burned out, she had to blow continuously until the fire caught hold and reached every corner of the wood pile.

Survival Science: The "Shpendlech"

Lighting a wood stove at 5 AM in a freezing house is an art form. The "shpendlech" mentioned were often made from "fatwood"—pine wood rich in dried sap (resin) that burns like a candle. If the fire died, the house stayed freezing and there was no breakfast. The text’s description of "blowing continuously" highlights the physical lung-power required just to start the day.

AI Generated

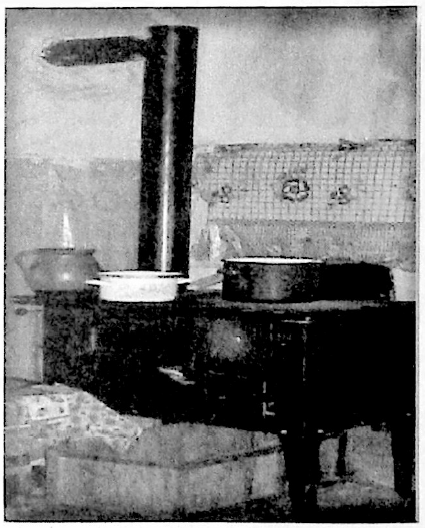

An oven—inside the fire burns, on top is for cooking

If the shavings and logs were dry enough, the whole process might take less than twenty minutes. Once the oven was heated, the woman placed a kettle on top, over the flame. The warm water needed to be ready for tea and to wash the children's faces when they woke.

Engineering: The Masonry Heater

These large ovens weren't just for cooking; they were the house's battery. Built of thick clay or brick, they absorbed the fire's heat all morning and slowly released it ("radiated") throughout the day and night. This "Thermal Mass" meant the house stayed relatively warm even after the fire went out, as long as the oven bricks were hot.

AI GeneratedA pre-dawn chill still hung in the air when she went out to the well, the rising sun illuminating her path with pale morning light. A turn of the screeching handle lowered the bucket into the deep hole, the clanking metal echoing far into the sleeping village.

A well in Sitchel, which served a neighborhood of several houses

Daily Grind: The Weight of Water

The text mentions using the river for laundry and the well for drinking. Why? Because water is heavy (8 lbs per gallon). Drawing 50 gallons from a deep well by hand-cranking a bucket is exhausting work. It was smarter to carry the clothes to the river than to carry the river to the house.

AI GeneratedThis water had to suffice all day for drinking and cooking; for *negel vasser*, נטילת ידים, washing dishes, and laundry, people used the nearby Iza River. Stealing a few minutes while the children still slept, the mother milked the cow, letting the fresh, white milk flow into a tin can. The warm milk wasn't ready to drink yet; it first had to be boiled to remove any bacteria.

Health: The Boiling Rule

Before pasteurization was common, raw milk could carry dangerous diseases like Tuberculosis. The "morning boil" was a critical safety step. Also, without homogenization, the cream would rise to the top instantly. This thick layer of cream was often skimmed off to make the butter mentioned later.

AI Generated

As soon as the little ones began to wake, the mother took them by the hand and led them out to the yard to the *beis hakisei* (outhouse). This wooden booth, similar to a shed, was nothing more than a deep hole in the ground, so young children could never be allowed to enter without an escort.

Sanitation: The Outhouse Reality

The beis hakisei was usually located far from the house to keep smells away. In the winter, a trip to the bathroom meant trekking through snow in sub-zero temperatures. To keep pests and smells down, families would throw lime (a white powder) into the hole, which chemically decomposed the waste.

AI GeneratedWith the freshly drawn water, small hands and faces were washed, and the children sat down to eat. For breakfast, the mother cut a few slices from the large loaf of bread baked the previous Friday, smearing it with *lekvar* (jam) or butter. Sometimes she toasted the bread on the fire, delighting the children with fresh *penits*. Along with the bread, the children ate some vegetables, perhaps a boiled egg, and washed it all down with a glass of boiled milk.

Food: Friday's Bread

The text notes they ate bread baked "the previous Friday." This was likely a dense, sourdough Rye bread (Black Bread). Unlike modern fluffy white bread which goes stale in a day, dense Rye bread could last for a week or two without molding, making it the perfect staple for a busy mother who only had time to bake once a week.

AI GeneratedIt was still early when the boys went to learn in the תלמוד תורה, a building with several classrooms. Classes consisted of 12 to 15 boys, grouped by age. The girls went to their own separate חדר, where they learned to read and *daven*.

During the חדר hours, the *melamdim* crammed as much as possible into the young heads, because only a short time later—at eight o'clock—the children had to be seated in the government school. Yet despite the minimal official Jewish education, the children absorbed a tremendous amount at home and even on the street, which breathed with Jewish life.

Education: The "Double Shift"

Jewish children in Eastern Europe effectively worked a 12-hour day. They attended Cheder (Jewish school) in the early morning before public school, and then returned to Cheder after public school until the evening. This explains why they had such high literacy rates but also why the text emphasizes how tired or busy they were.

AI GeneratedIn the public school, Jewish children participated in all subjects—geography, history, spelling, and mathematics. Twice a week, however, when the school provided classes on Christianity at the end of the day, the Jewish students were permitted to go home early.

Historical Trivia: The "Golden Hour"

The government required religious studies in public school, but they only paid for a Christian teacher. Since the village school didn't hire a Rabbi, the Jewish kids were legally excused during that hour. This created a rare "loophole" where the Jewish students actually got out of school earlier than their gentile neighbors.

AI GeneratedRegarding his Jewish school friends, the aforementioned Dr. Petrescu writes: "[They] were more talented in mathematics than in other subjects... Jewish students could always be used as a model of correct, good behavior and politeness. They came to school with more punctuality than the Romanian students..."

Linguistics: The Trilingual Child

A typical 8-year-old Jewish child in Sitchel was a linguistic genius by modern standards. He spoke Yiddish at home, Romanian in the street with neighbors, Hungarian with the officials/gendarmes, and read Hebrew (Lashon Kodesh) in Cheder. Their brains were constantly switching codes.

AI GeneratedIn their free time, after חדר and school, the children spent their hours in the lap of nature. In the summer, boys ran carefree through the fields or bathed in the cool, bubbling Iza River. Even the frosty winter couldn't keep them indoors; the surrounding mountains became the most exciting playgrounds. Children happily slid down the snowy slopes on sleds, while the rowdier village boys threw snowballs at one another, at the other children, and at any *shlimazel* passing by.

While the children were out, the mother remained busy with her endless tasks. Every day, the village woman tended to the garden—planting, watering, or picking ripe fruit and vegetables. The cows in the yard also demanded care. Her overworked hands never stopped moving as she went from one duty to the next; yet, these נשים צדקניות still found time to say תהלים and do חסד with their neighbors.

Culture: The "Vegetable Patch"

When the text mentions a "garden," don't picture flowers. A village garden was a survival grid. Women grew onions, garlic, carrots, beans, and potatoes—hearty crops that could be stored in the cellar for winter. If the garden failed, the soup would be just hot water for the next six months.

AI GeneratedPreparing Food

To buy butter for bread, one had to be a גביר (wealthy man). Those who could churned their own milk to produce homemade butter. Some families had a "butter barrel"—a wooden churn wide at the bottom and narrow at the top, fitted with a plunging stick. It took endless energy and time to churn the milk with the necessary speed until it hardened into spreadable butter.

Economics: Butter

The text mentions that buying butter was for the wealthy. This is because butter was a "cash crop." Most families sold their butter at the market to buy shoes or candles. Making it was hard labor: churning by hand takes 30–60 minutes of heavy plunging, often done by children.

AI Generated

Preparing "Povidl," as *lekvar* (jam) was called, was no light task either. Neighbors would gather in a yard, sitting around a large iron pot. Together, the women cut up plums, checked them thoroughly for worms, and threw them into the pot. The plums cooked over an outdoor fire all night long, with one woman staying awake to stir constantly; if left alone for even a moment, the mixture would harden. When the *lekvar* was ready, the neighbors divided it among themselves, pouring it hot into glass jars. For a long time after, the children would lick their lips over the *Povidl*, preserved for many tasty breakfasts.

Food Science: The "Povidl" Trick

Sugar was an expensive luxury, so how did they make jam? By boiling the plums for 24 hours, they evaporated the water and concentrated the natural fruit sugars. This created a dense, dark paste that wouldn't spoil, even without adding extra sugar. The all-night stirring sessions mentioned were also major social events for the women, similar to a "quilting bee."

AI GeneratedAt midday, the children returned from school for the main meal. Those who could afford it made goulash—a stew of meat chunks—or a fine "paprikash," consisting of meat and sautéed onions in a pan, with potatoes added later.

"Mamaliga" or "Puliska"—a cornmeal dish—was served for supper, and sometimes for breakfast as well. On Thursdays, many women made "chipkelech bandlech"—cooked beans topped with sautéed onions, with pieces of meat or liver added if the budget allowed.

Culinary History: "Poor Man's Bread"

Mămăligă (cornmeal porridge) is the national dish of the Romanian peasantry. Wheat doesn't grow well in the steep mountains, but corn does. Wheat flour had to be imported from the plains, making it expensive. For a village Jew, eating white wheat bread (Challah) was a sign of Shabbos, while corn was the daily fuel.

AI GeneratedTradition: The "Thursday" Bean

Why beans on Thursday? Thursday night is Leil Shishi, traditionally a night when men and boys stayed up late to study Torah or prepare for Shabbos. Beans (protein) provided slow-burning energy for the long night. It was also a cheap way to stretch a meal when the meat supply was running low before the fresh Shabbos shopping.

AI Generated

At the end of summer, merchants arrived in the village with wagons full of cabbage. Since it was an inexpensive staple, women bought it in large quantities to pickle immediately for the winter. They cut the cabbage and packed it into glass jars with garlic and salt, placing a slice of bread on top before sealing the lid tight. The jars were usually placed by a sunny window to speed up the fermentation. The cabbage kept for a long time without needing an icebox.

Health: The Vitamin C Saver

Fermenting cabbage into sauerkraut wasn't just about taste; it was about survival. In winter, there were no fresh fruits or vegetables. Sauerkraut retains Vitamin C, protecting the village from diseases like Scurvy during the long months when the ground was frozen.

AI GeneratedScience: Ancient Probiotics

The text mentions adding a slice of bread to the cabbage jar. This introduces yeast and bacteria to kickstart the fermentation process. Without knowing it, these women were masters of microbiology, creating "probiotic" foods that kept their families' digestion healthy during a winter diet of heavy fats and carbs.

AI Generated

An essential kitchen tool was the *shteisel*—an iron mortar and pestle. With this, one pounded hard challah into crumbs, crushed garlic, or broke apart hardened blocks of salt, sugar, and spices. The pestle looked identical on both ends, used to pulverize whatever was needed.

Tools: Why the Hammer?

Why did they need a heavy iron tool for sugar? In that era, sugar wasn't sold in bags of granules. It came in large, hard cones called "sugarloaves" that were as hard as rock. You had to physically smash a piece off to put it in your tea.

AI GeneratedEvery garment lived through many incarnations, from the moment it hit the dirty laundry bin until it returned to the closet. Laundry was soaked in soapy water overnight. The next morning, the rinsed clothes were transferred to a huge pot and boiled over a flame with "loig," a homemade cleaning agent made of soap and ash.

Chemistry: Homemade "Loig"

Loig is the Yiddish word for Lye. Housewives made their own powerful detergent by pouring water through wood ash. This created a chemical that dissolves grease, but it was dangerous. Boiling lye is caustic and can burn skin, making laundry day one of the most hazardous chores of the week.

AI Generated

Village women washing laundry in the Iza River

Lucky to live near a river, the women of Sitchel carried the boiled laundry down to the Iza. Wearing tall boots, they waded into the water and stood near a stone. There, they laid out the wet clothes and beat them with a wooden board to release the dirt. Then came the scrubbing, washing, and rinsing until everything was completely clean. This river work required constant vigilance; a young child could never be trusted with it. A moment of distraction could see a garment swept away instantly by the current—and who could afford such a loss?

Daily Life: The River "Machine"

Washing clothes in a river wasn't peaceful; it was violent. The text mentions "beating with a board." This mechanical action mimics what a washing machine agitator does today—forcing water through the fabric to knock dirt loose. In winter, this meant standing in freezing water, often breaking the ice to get the job done.

AI Generated

After rinsing, the laundry went back into a pot of water over the fire. This time, however, it was "blue water"—mixed with a special blue tablet from the pharmacist that whitened the fabric. Finally, the clothes were rinsed again with starch water and hung outside to dry.

Science: The "Blue" Optical Illusion

Before bleach existed, they used "Laundry Bluing." White fabric turns yellow over time. Blue is the opposite of yellow on the color wheel. By adding a tiny bit of blue dye to the water, they neutralized the yellow tint, tricking the eye into seeing a brilliant, stark white.

AI Generated

In winter, when the sun was too weak to dry anything, the wet laundry was hung in the בוידעם (attic). Once dry, the clothes were ironed with a coal-heated iron. Thanks to the starch, they came out stiff and smooth, ready to be folded and put away in the קרעדענץ.

Tools: The Heavy Iron

Ironing was a workout. The iron was a hollow metal box filled with glowing hot coals. You had to constantly wave it to keep the coals hot, but not so hot that they burned the fabric. The starch mentioned was likely made from potato water, stiffening the collars to look formal despite the poverty.

AI GeneratedSewing and mending was an entirely separate occupation. Old clothes were taken apart and remade into new ones, large holes were patched, and warm sweaters and scarves were carefully hand-knitted by the mother.

Sustainability: "Turning" a Coat

When a suit jacket got worn out, they didn't throw it away. They would "turn" it—literally ripping the seams apart, flipping the fabric inside out (where the wool was still fresh and unfaded), and sewing it back together. A good coat could last 20 years this way.

AI GeneratedPoverty and Invention

They darned socks at night by candlelight

A single large glass often played many roles in the household. It held the wine purchased for קידוש and הבדלה, and if cooking fat ran low, the shopkeeper would fill that very same glass with oil. If a goblet broke, no one rushed to replace it; this glass served just fine for a לחיים.

And late at night, when the children were fast asleep and the mother sat mending socks by candlelight, the glass found yet another purpose: slipped inside a sock, it created a smooth surface for the needle to do its work.

Daily Life: The Glass Hack

To fix a hole in a sock ("darning"), you need to stretch the fabric over a hard, round surface so the needle doesn't sew the two sides together. Wealthier people bought a wooden tool called a "Darning Egg." The poor simply used a smooth drinking glass—a classic example of using one tool for everything.

AI GeneratedAn average cottage in Sitchel contained only the bare necessities. No one hoped for a six-room house, and fresh clothes every day were unheard of. These weren't problems to be solved, but simply unchangeable facts of life. Yet premature aging was rare, simply because anxiety had no place in village life.

Chapter Three — A Shabbos in the Village

A Shabbos in the Village

Given the limited conveniences of the time, preparing for a שבת in the village demanded far more effort than it does today, but it was worth every ounce of exertion. שבת in the warm, homey atmosphere of the village was a refreshing break from the grueling schedule—the light at the end of the tunnel for the hardworking Jew.

Preparations for the שבת meal began on Thursday morning—early enough to finish on time, yet late enough to ensure the food remained fresh. The day started with a trip to the market, where hands were filled with כל טוב—fish, fruit, vegetables, and a fine chicken.

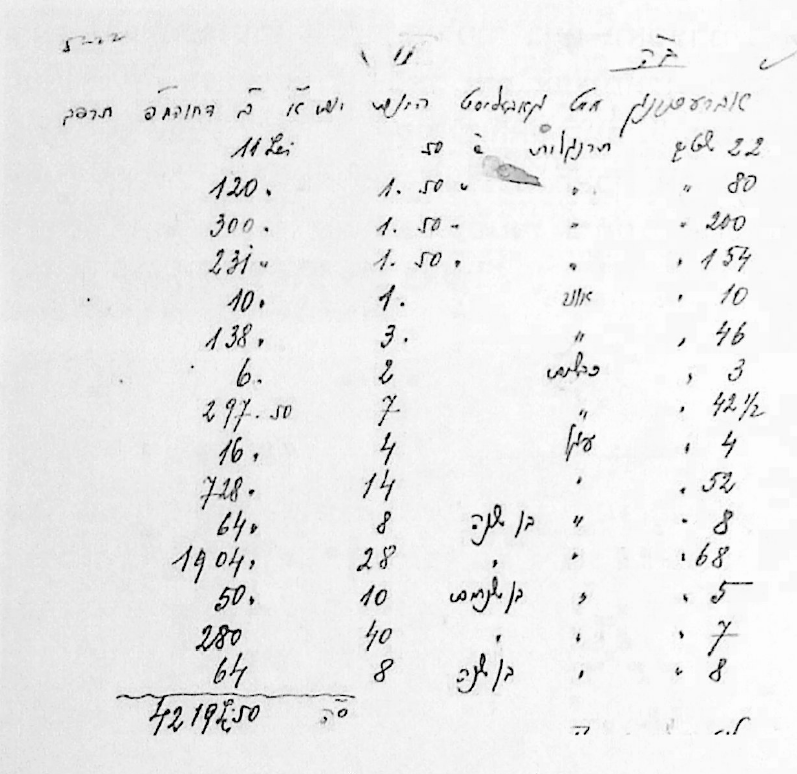

The next stop was R' Tzvi Meyer the שוחט. Once the chicken was slaughtered, one had to pay the גאבעלע—a ticket issued by the קהל specifying whether the animal was a chicken, a duck, or cattle. The שוחט would later submit these tickets to the community to receive his salary. Residents paid the קהל directly; the community leadership took a percentage for administrative costs and paid the rest to the שוחט.

Economics: The Meat Tax

The "Gabele" mentioned here was a ticket system used to collect taxes. In Eastern Europe, the Jewish Community Council (Kehilla) relied on the tax on Kosher meat (the Korobka) to fund almost everything—schools, the Mikvah, and charity. If you didn't buy a ticket, the Shochet couldn't kill your chicken, ensuring no one could dodge the tax.

AI Generated

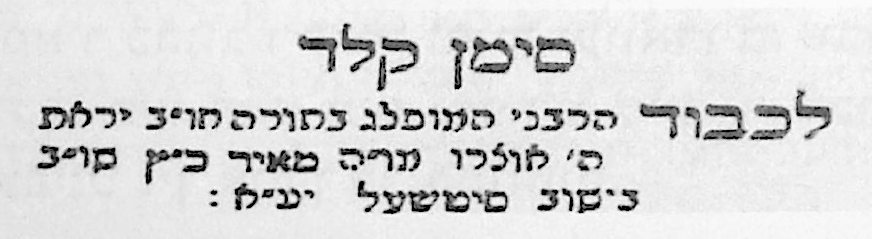

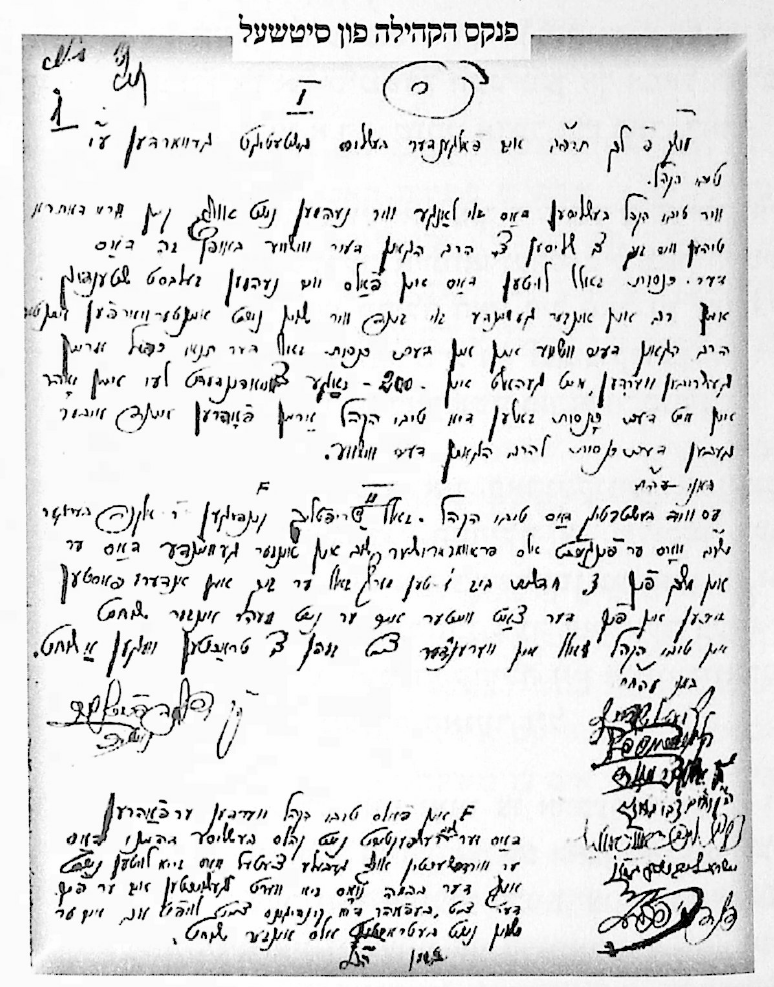

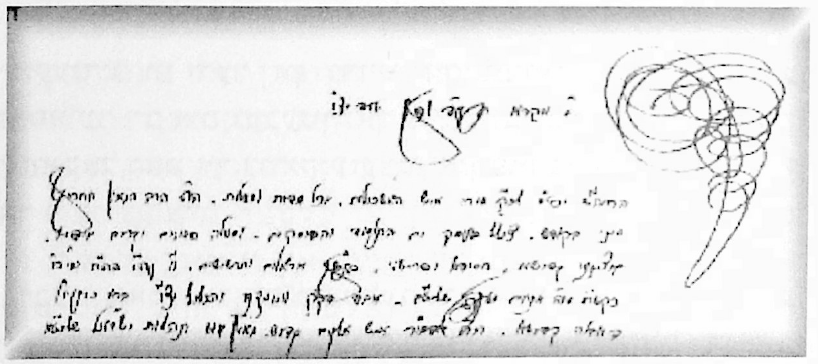

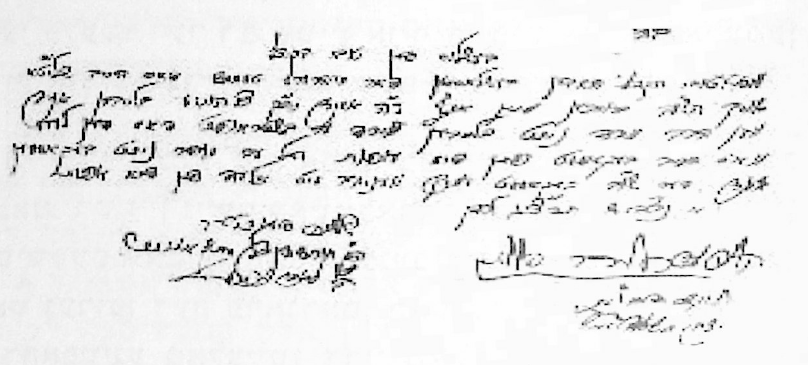

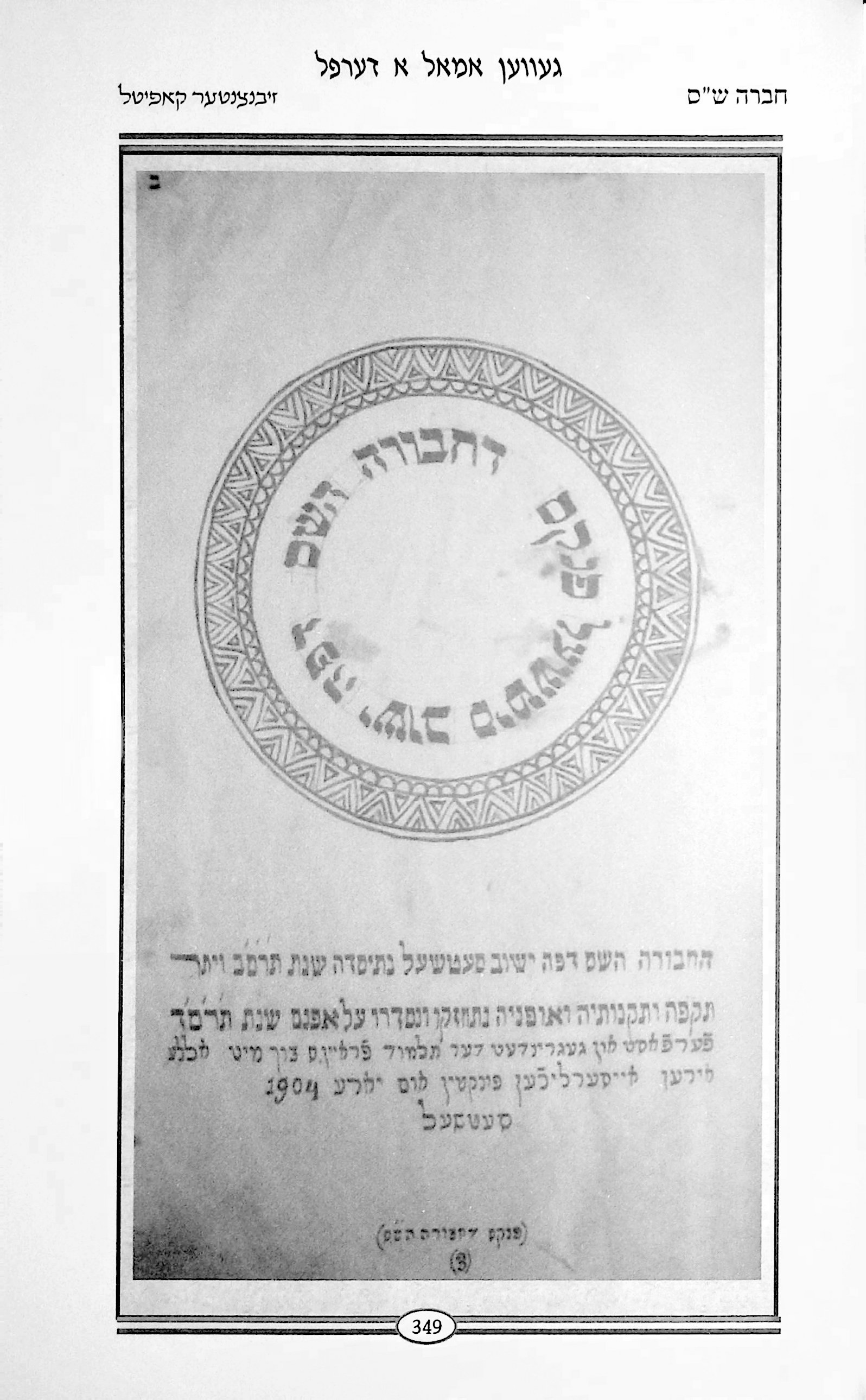

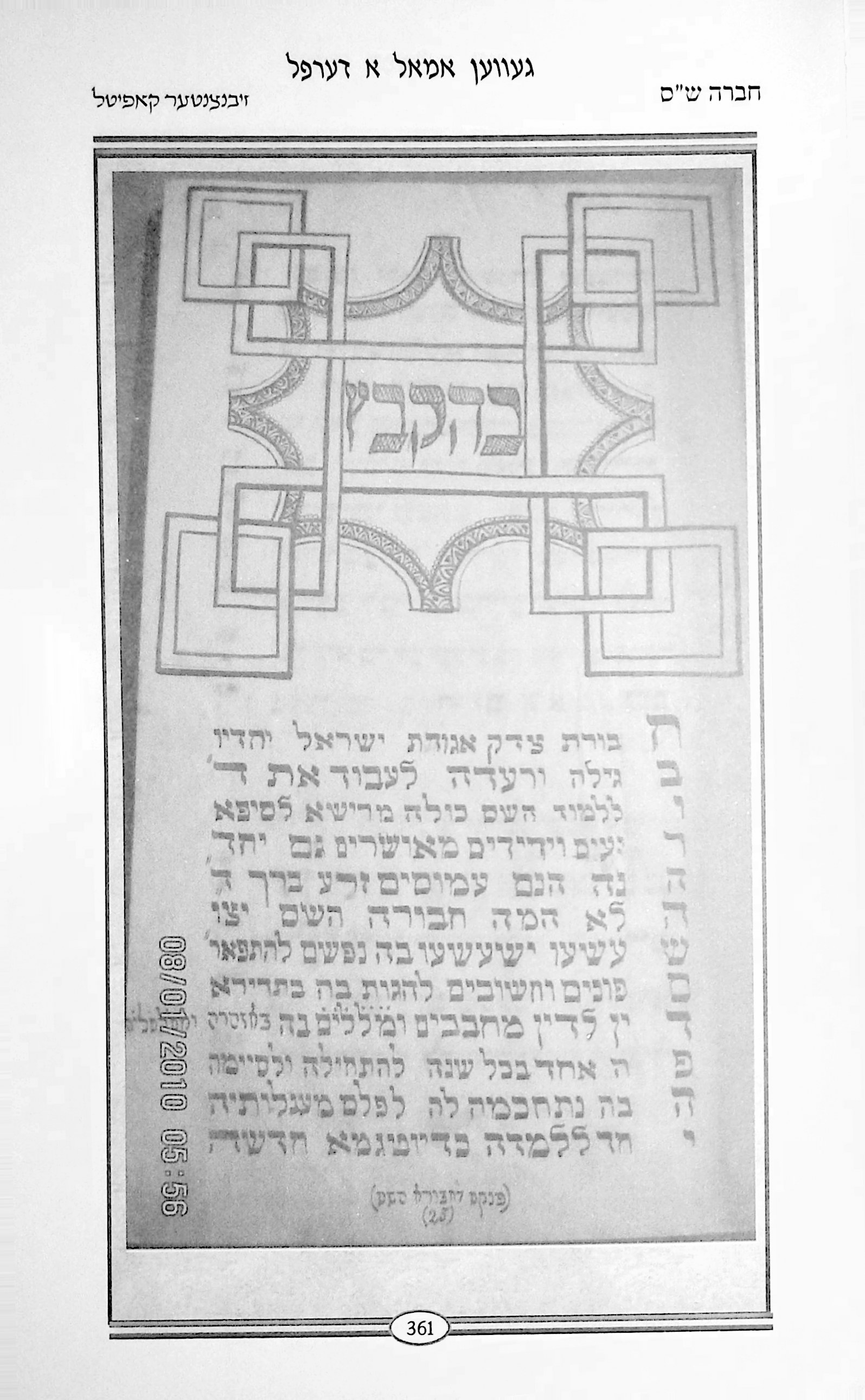

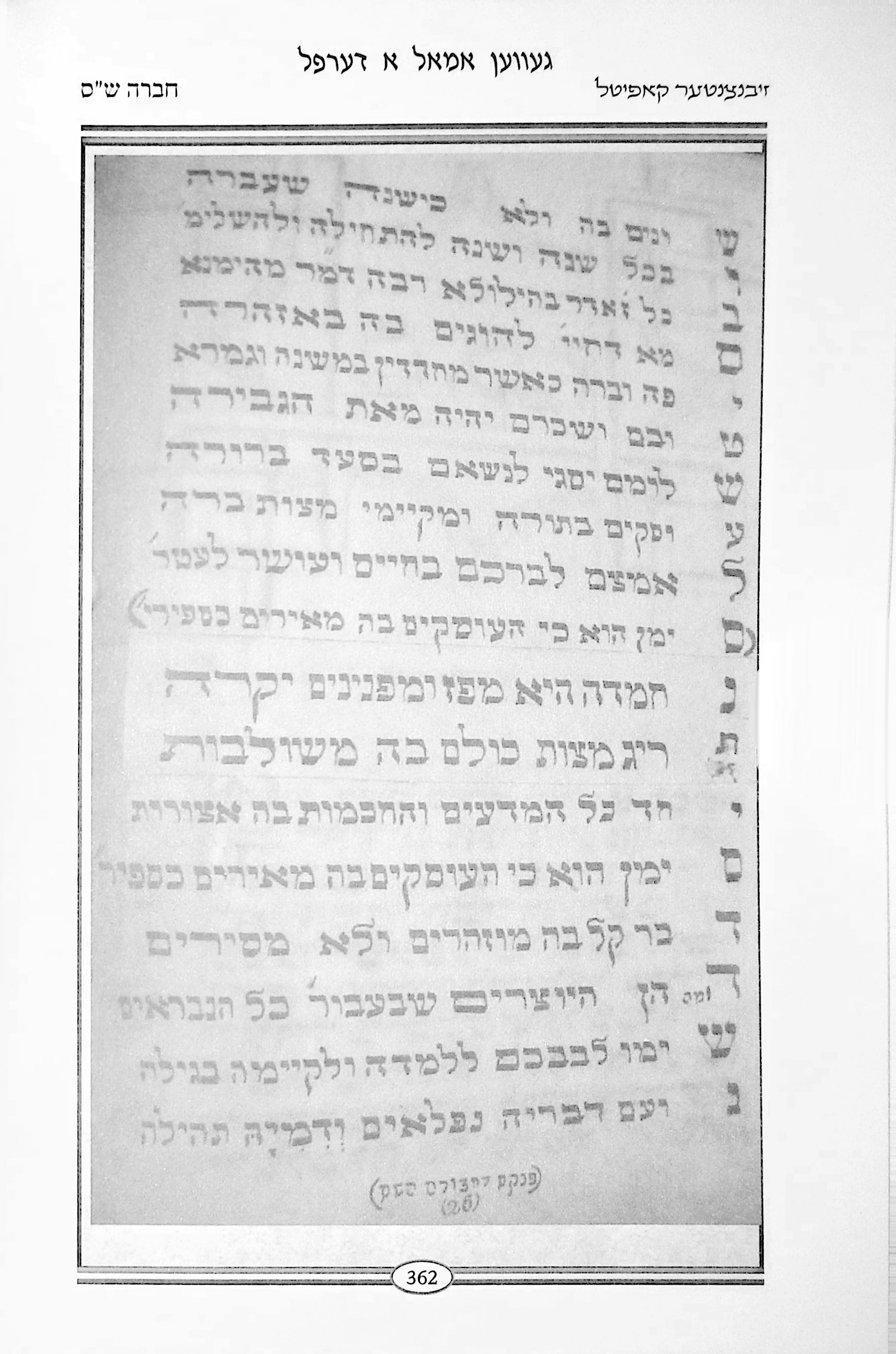

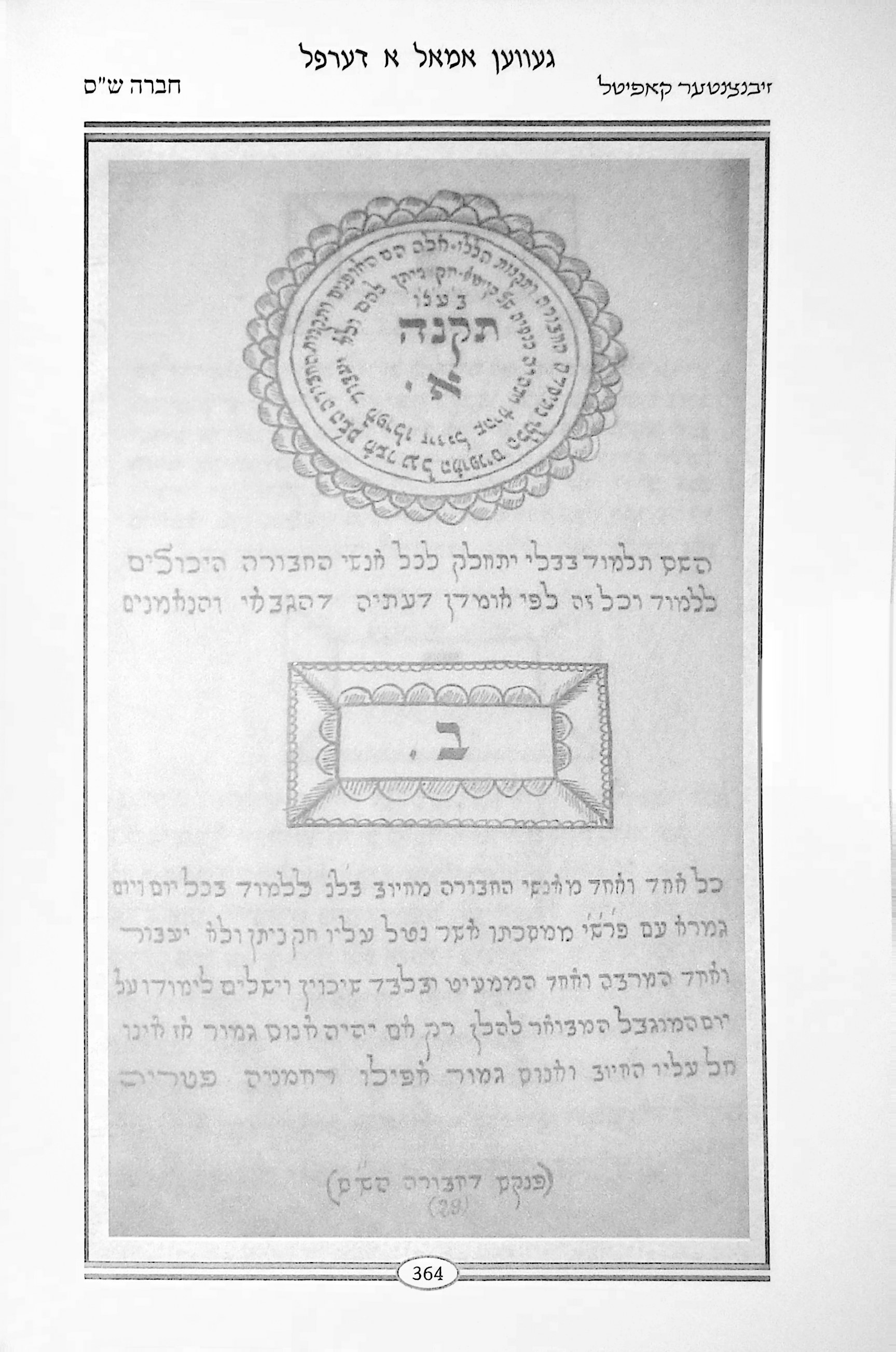

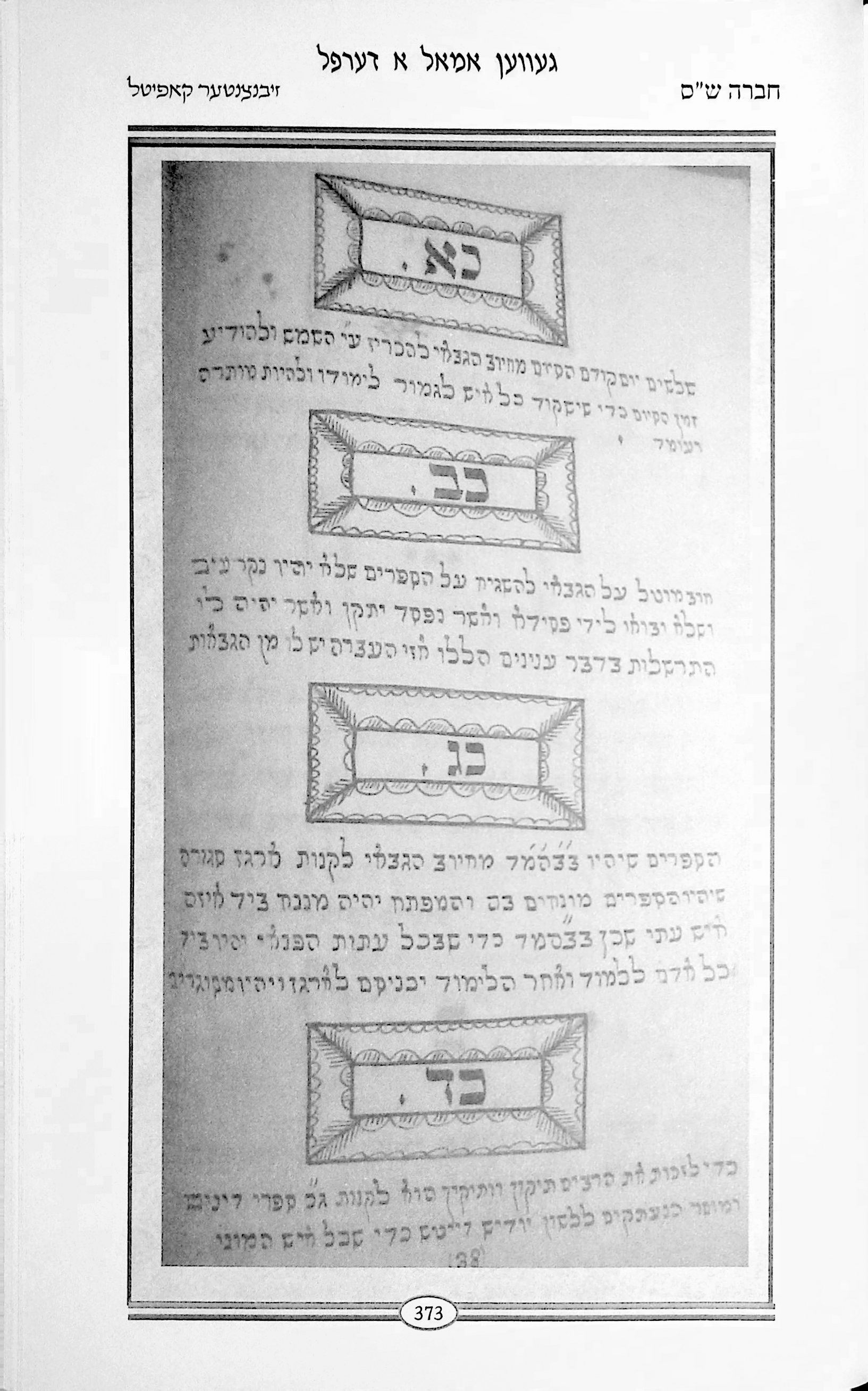

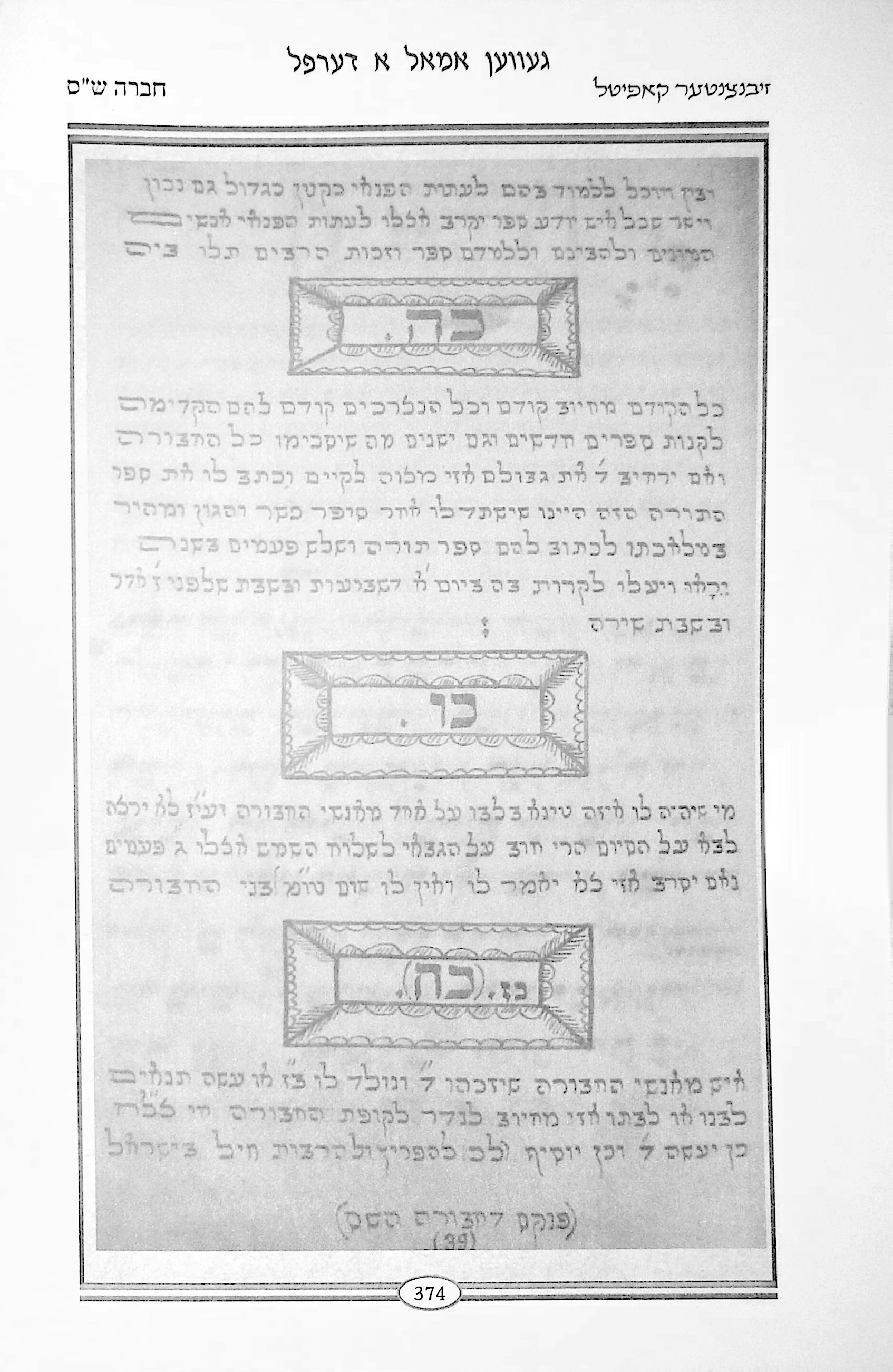

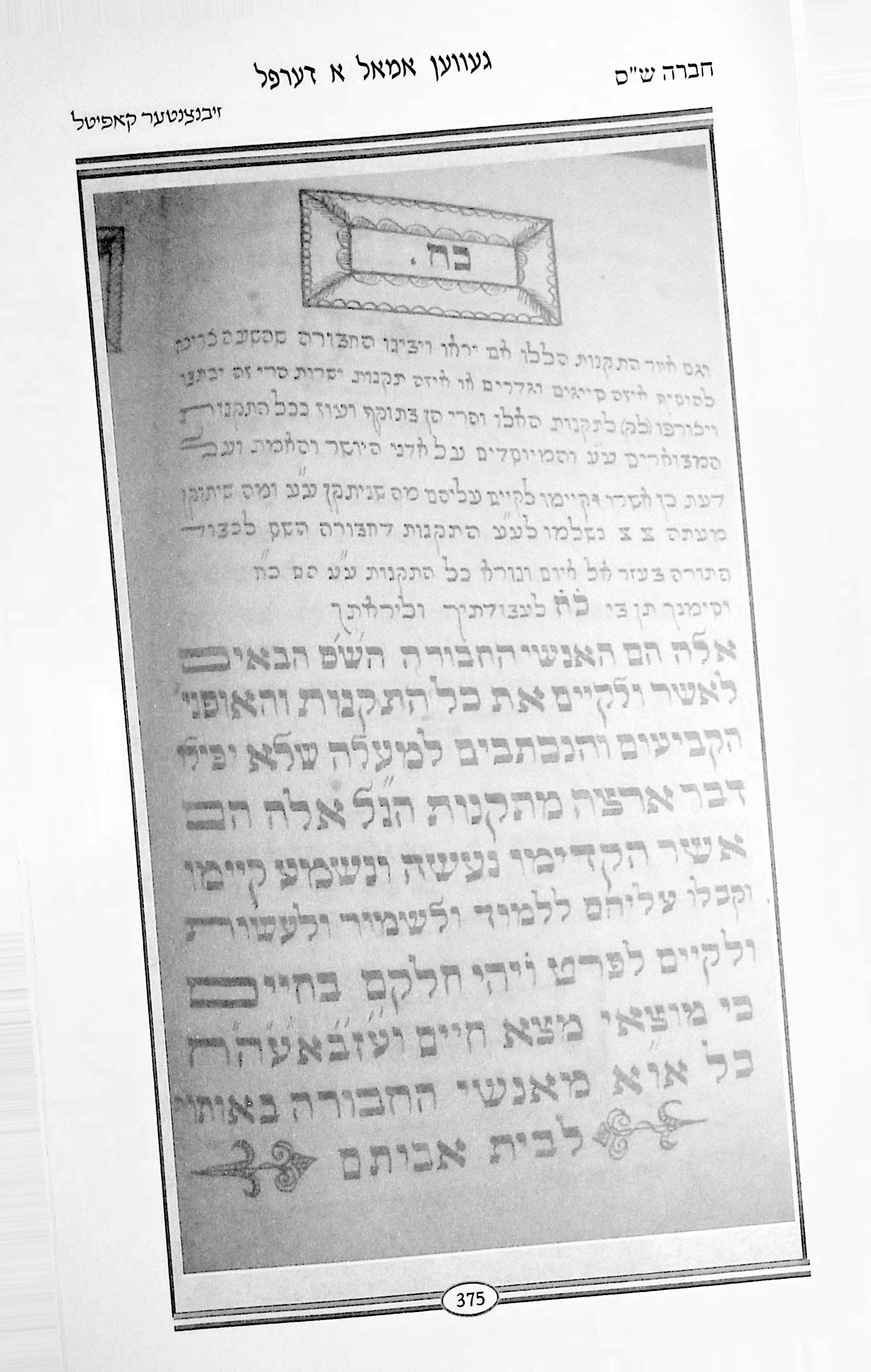

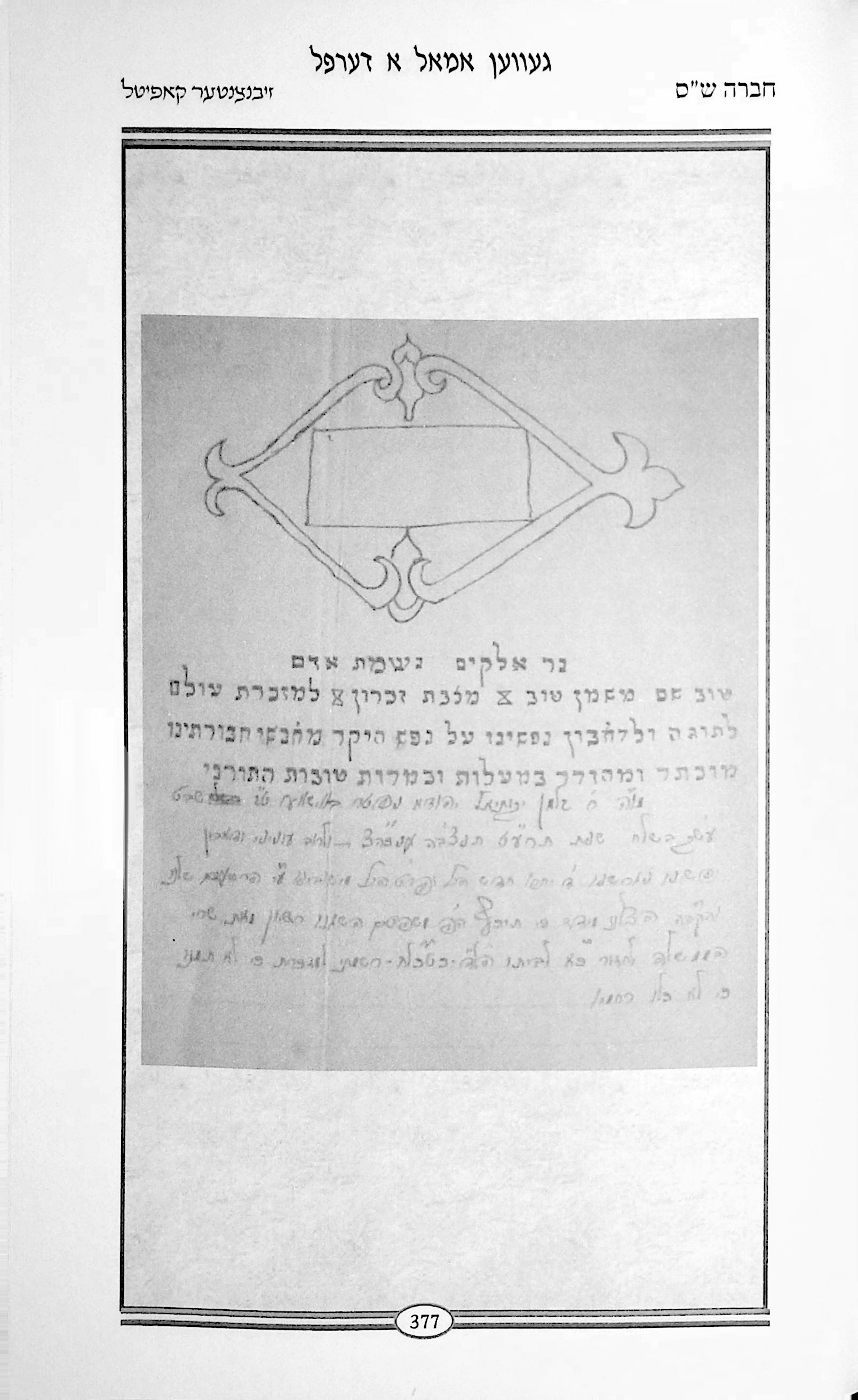

Pinkas HaKehillah—Accounting of the גאבעלעs with the Shochet

The moment the mother returned home with the chicken, the entire family—from the toddlers to the elders—was harnessed for the work: plucking feathers, butchering the bird, and salting every piece of meat thoroughly. The meat was then set aside in a bowl for over an hour to drain the blood. After rinsing it well several times, the mother set the chicken to boil לכבוד שבת.

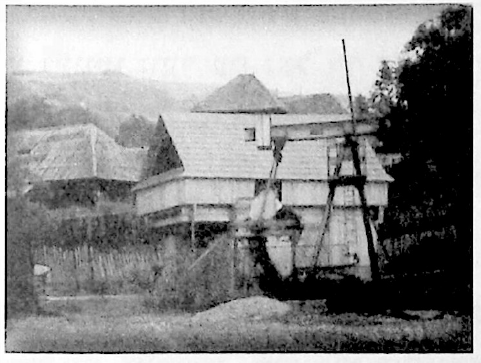

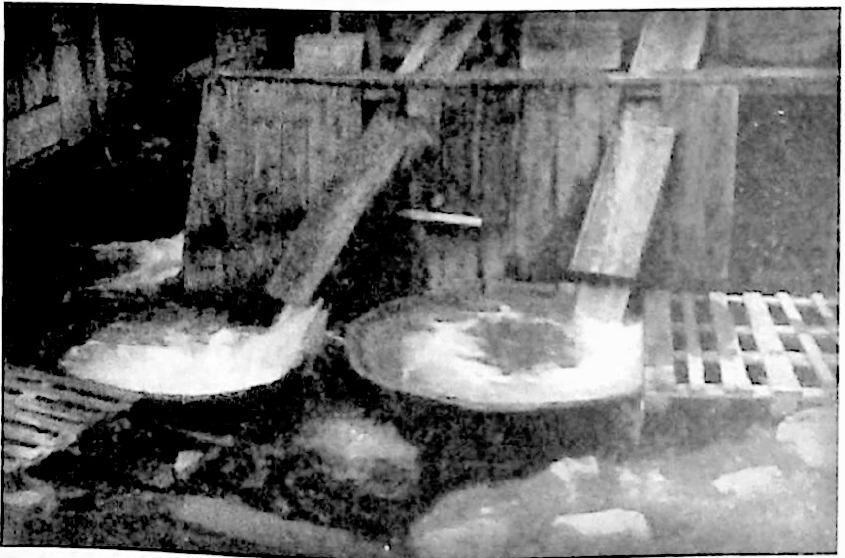

The watermill station in Sitchel

Baking חלות began with buying wheat, as ready-made flour was not sold in Sitchel. The kernels were taken to the miller at the watermill on the Iza River to be ground. What returned could barely be called "flour" yet; the ground kernels had to be sifted multiple times until clean, snow-white flour emerged, ready for baking.

Current Event: The Mill Still Stands!

The watermill mentioned here is the famous Moara lui Mecleș (Mecleș Mill) in Săcel. Built around 1907, it is still standing and powered by the Iza River today. It is one of the last functioning watermills in Europe and is now a popular tourist attraction.

AI GeneratedFood Science: White Flour Luxury

We take white flour for granted, but historically, "Whole Wheat" was the food of the poor because it was easy to make. White flour requires sifting out the bran and germ, which is labor-intensive and wasteful (you lose volume). Having pure white Challah on Shabbos was a status symbol, showing you could afford to waste the "rough" parts of the wheat.

AI GeneratedBuying yeast was a saga in itself. Sitchel was one of those villages where the community held a monopoly on yeast and set the prices, as the profits were a significant source of revenue for the קהלה.

Economics: The Yeast Monopoly

Why control yeast? Because every family baked bread every week. By holding a monopoly on yeast, the Community Council guaranteed a steady stream of income to pay the Rabbi and maintain the Synagogue. It was a form of "voluntary tax" that was impossible to avoid if you wanted to eat bread.

AI GeneratedEarly Friday morning, the women stood ready with their ingredients, manually kneading dough made from ten or twenty kilos of flour in the "מילטער"—a massive wooden trough. This yielded enough dough for several beautiful, large חלות and בילקעלעך (rolls).

Daily Life: The "Milter"

A "Milter" (kneading trough) was a piece of furniture, not a bowl. It was often a large wooden box on legs. Kneading 40 lbs (20 kilos) of dough by hand is physically exhausting—like a heavy gym workout—and it had to be done weekly by the women of the house.

AI GeneratedSince Sitchel homes had no private ovens for baking—only a space over the fire for cooking—the dough was carried to the local baker every Friday. While the חלה dough rose, a second batch was kneaded, this time from cornmeal (a much cheaper option), to make the bread that would be sliced and eaten throughout the week.

Two more fresh batches of dough followed soon after: one for לאקשן and another for פערפל. A skilled בעל הבית'טע also managed to add several cakes, flatbreads, פלאדן (pastry filled with cheese and green onions), and various types of cookies.

Fluden

Culinary History: Fluden

The text mentions "Fluden." This is a classic Ashkenazi pastry, often layered with cheese or fruit. In Hungary and Romania, it was a staple Shavuos or Shabbos treat, similar to a dense strudel or lasagna made of dough and sweet fillings.

AI GeneratedOnce the חלות were braided and sprinkled with poppy seeds, the entire transport of dough was carried to the baker, who baked it for a modest fee. Later, the goods would return—browned, fragrant, and deliciously warm.

Meanwhile, plenty of work remained in the kitchen. The fish had to be chopped, and a portion of it ground in the hand-mill—a tool that held a place of honor in every kitchen, especially on ערב שבת with its varied culinary tasks. This ground mixture was stuffed inside slices of fish to cook together (this is the origin of our "Gefilte Fish"). In the winter, when fresh fish was sometimes unavailable, meat was ground in the mill to create "false fish" to serve at the meal instead.

Food History: "False Fish"

Sitchel is in the mountains, far from the ocean or large lakes. Fresh carp was hard to get in winter. "Falshe Fish" (False Fish) was ground chicken or veal breast, seasoned with onions, pepper, and sugar to *taste* like fish. It allowed the poor or isolated to keep the custom of eating fish on Shabbos, even without the actual fish.

AI Generated

Hand Mill

Once the fish, soup, kugels, and compote were cooked or simmering on the flame, the house cleaning began. Every corner was dusted, spiderwebs were swept away, and fresh sand was spread over the earthen floor לכבוד שבת.

Interior Design: The Sand Floor

Most homes in the village had floors made of packed dirt, not wood. To make it festive for Shabbos, they would sweep it clean and sprinkle fresh, yellow river sand over it. This brightened the room and trapped dirt, acting like a disposable carpet that could be swept out on Sunday.

AI GeneratedWhen the clock struck חצות, no announcement was needed; the shift was felt in the air. The weekday rush ground to a total halt. The water carrier set down his cans, the milkman put away his jugs, the woodchopper dropped his axe, the blacksmith extinguished his fire, and the wagon driver sent his horses to the stable. The wire-worker, glazier, shoemaker, carpenter, lime-burner, tailor, tinsmith, and shopkeeper all finished their work, locked their doors from the outside, and hurried home.

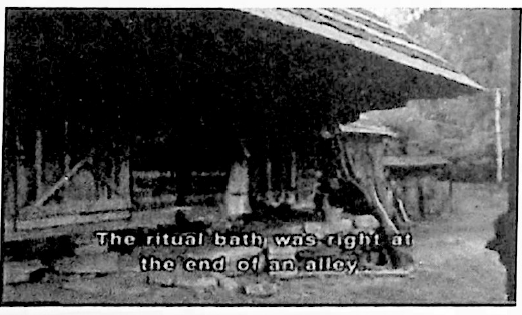

A new kind of rush took over—a זריזות fueled by joy and holiness as the Jews prepared for the approaching שבת קודש. Young men could be seen running to the מקוה to catch a טבילה, holding clean white shirts under their arms, with their children striding alongside them.

The mikvah alley in Sitchel

The מקוה was built close to the river, which supplied its water. In the center of the pool stood a square iron box filled with wood to heat the water. The temperature was never uniform; around the box it was decent, but further away, the water remained chilly. While wealthier cities might have afforded a wood stove to heat the room, in Sitchel, the raging winds blew through the cracks. Every few minutes, a shivering, wet Jew would touch the stove just to check if it was actually working, though it did little to combat the frost.

Rusty nails on the wall served as clothing hooks; if a nail was bent or loose, clothes were simply piled on the bare bench. In a small village like Sitchel, a separate boiler for showers was a luxury no one had. Instead, a bucket was used to scoop water from the מקוה for rinsing off after soaping up.

Architecture: The Mikvah Stove

The "iron box" in the water is a submerged heater. This was dangerous but effective. A fire burned inside the metal box which was underwater, transferring heat directly to the pool. It was far more efficient than heating water outside and piping it in, but if the seals leaked, it could fail catastrophically.

AI GeneratedEmerging from the מקוה, the men looked transformed. Gone were the muddy weekday work clothes, stained hands, bent shoulders, and weary faces. In their place appeared immaculately clean garments, straight backs, and beaming, scrubbed faces—a reflection of the fresh נשמה יתירה preparing to enter the Jew and transform him into a בריאה חדשה.

As darkness fell and שבת knocked at the door, the men quickly grabbed their earthen pots of cholent and carried them to the baker. The baker placed the pots of every villager into the oven, one after another. Beyond his baking skills, he needed a sharp memory to know exactly when each family would come to collect their cholent on שבת morning, placing the pots in the oven accordingly so he wouldn't have to dig out the back rows first.

Community: The Baker's Memory

The village baker's oven was the community's "Slow Cooker." Hundreds of identical clay pots were stacked inside. The baker didn't use tickets; he knew every family's pot by its shape, a chip in the lid, or the smell of the stew. A mistake here meant a family went hungry on Shabbos, so the baker's memory was legendary.

AI GeneratedOnce all the pots were stowed, the baker sealed the oven with clay to trap the heat. The sun sent its final parting rays through the window, signaling the day's end. Suddenly, the semi-dark room was illuminated by a row of radiant flames as the שבת candles took over with their holy glow.

Halacha: Sealing the Oven

Sealing the oven with clay (Lehm) served two purposes. Physically, it trapped the heat so the Cholent would cook overnight without a fire. Halachically, it prevented anyone from stoking the coals on Shabbos (a prohibition called Gezeirah Shema Yechate), ensuring the food was kept warm permissibly.

AI GeneratedWith a warm "גוט שבת," the men stepped out of their homes soon after הדלקת הנרות, walking the sandy streets in their בגדי שבת. Their heads were crowned with flat שטריימלעך—some so worn one would have to squint to find two hairs left on them. Faded רעזשוואולקעס covered patched caftans (bekishas), often heirlooms from a previous generation. Yet the flavor of שבת brought a freshness and splendor that the finest garments could never achieve.

Fashion: The "Flat" Shtreimel

Shtreimels (fur hats) have changed shape over time. In the 1920s, the Hungarian style was low and wide ("Flat"), unlike the tall, fluffy hats popular today. The text notes they were "worn," because a real beaver-fur hat cost a fortune—often a year's wages—so they were passed down from father to son for generations.

AI GeneratedWith quick steps, the Jews turned into the בית המדרש, children holding tight to their fathers' coats. Some went to the large central shul, others to the תלמוד תורה Shul behind the main street, and the workers to their own שטיבל in a side alley.

Across the village, the heartfelt, longing tones of שיר השירים drifted from the Batei Midrashim. "*אל תראוני שאני שחרחורת, ששזפתני השמש!*" the rushed, overworked laborers cried out with feeling. "Do not look down on me because I am blackened, tanned by the sun, from standing and toiling to bring bread to my children..."

“הודו לד׳ כי טוב”—the davening began with fire. The אהבת ה׳, hidden away in a corner during the long work week, burst forth from the heart. The Jew ascended to a new world where work, expenses, and money played no role.

After davening, people lingered in shul. Perhaps a stranger had arrived who needed a place for the שבת meal? Though there was no great abundance at home, no one made calculations when it came to hosting an אורח. Walking home in groups, the men discussed the weekly סדרה. One shared a thought from his yeshiva days, another added something he'd read, a third offered his own חידוש. No matter what occupied their minds during the week, on שבת, it was time for Torah.

After a warm "שלום עליכם" and "אשת חיל," the father made קידוש. The cup was often filled from the single large glass of wine purchased at R' Moshe Chaim Malik's to serve for both Friday night קידוש and הבדלה. With the blessing of בורא פרי הגפן, the בעל הבית discharged the obligation for the entire household; the children received only a tiny drop on the tip of their tongues, barely enough to taste.

Economics: The Cost of Wine

Why did the children only get a drop? Because wine was an imported luxury. Grapes don't grow well in the high Carpathian mountains. Wine had to be brought in by wagon from the warmer Tokaj region of Hungary, making every drop precious and expensive.

AI GeneratedAh, how sharp and true the words "המבדיל בין קודש לחול" (Who separates between holy and profane) felt! Sitting at the table with family in a calm, pleasant atmosphere, singing cheerful ניגונים with spiritual delight, the contrast was stark. While gentile neighbors spent their rest day at the tavern, drinking until they couldn't walk, the Jew filled his שבת with inner, eternal pleasures, satiating soul and body alike. How different was the Jew's workday, aimed at earning a living for עבודת ה'; and how different was his day of rest, used to elevate himself to higher spiritual planes.

After a tasty meal and a refreshing sleep, the בית המדרש filled up again. As on every שבת morning, a large מנין gathered to say תהלים, led by R' Moshe Mendel, son of R' Nochum Ganz. The שליח ציבור recited the verses aloud, accompanied by hot tears and pleas for the wellbeing of all Jews.

From early morning, the walk to and from the מקוה was accompanied by a symphony of sweet sounds drifting from open shutters. Here a Jew was מעביר סדרה; there a father hummed a Gemara ניגון while testing his children; and from a distance, a תהלים sayer could be heard crying out with fire, "*ושועתי אליך תבא!*"

The בית המדרש filled, and the congregation entered into a warm תפילת שחרית. פסוקי דזמרה was accompanied by cheerful singing, and upon reaching נשמת, the דביקות rose to new heights. The village Jews cried out the heartfelt words with deep emotion, following the נוסח they had heard at their Rebbe's court.

Upon returning home, the father made קידוש on a glass of schnapps or beer, and the family sat down to a fresh, tasty meal. The father and his sons injected a חסיד'יש flavor into the gathering, teaching the younger children what they had observed by the Rebbes. The meal came alive with stories from the *תורת חיים*, heard from a grandfather, or tales of the *צמח צדיק*. Others related anecdotes of the holy *קדושת יום טוב* or *ייטב לב* zy"a. A voice would rise in a warm melody heard recently at a Rebbe's טיש, awakening deep longing for those moments of inspiration.

After the egg-and-onion course, a child was sent to the baker to fetch the cholent pot. If the village עירוב wasn't כשר that week, a gentile was sent to carry it, always accompanied by a child to keep an eye on the pot and avoid any חששות of בשר שנתעלם מן העין. The gentile neighbors were also relied upon to milk the cows, heat the homes, or draw water, gladly performing these favors in exchange for fresh rolls and pastries.

Social Structure: The "Shabbos Goy"

The "Shabbos Goy" was an integral part of Jewish infrastructure. This wasn't just a random favor; it was a steady job paid in baked goods (which were superior to the peasant bread). The gentile neighbor knew exactly what was permitted and forbidden, acting as the "hands" for the Jewish community on their day of rest.

AI GeneratedOn sunny שבת afternoons, the boys gathered with their friends and the girls with theirs, spending long hours with youthful energy. Dressed in fine בגדי שבת and holding hands, they strolled through the village roads and alleys, returning home tired but cheerful in time for מנחה and שלש סעודות.

And so שבת passed for the village Jew with pleasure and peace of mind—an island of rest in the hustle of the week. He drew fresh vitality and renewed strength, ready to face another week of toil.

Yamim Noraim

Spending ראש השנה with the Rebbe was the dream of every village Jew, though few had the means to fulfill it. The journey was long and exhausting, and not everyone could leave their families for so long. But even those who didn't have the זכיה to greet the Rebbe on ערב יום טוב conducted their תפילות in an uplifted atmosphere.

In the large Sitchel בית המדרש, warm and capable בעלי תפילה led the services: the שוחט R' Tzvi Meyer Foigel, R' Eliezer Yaakov Ganz, the מלמד R' Chaim Yossel Ovitz, and R' Levi Yitzchok Steinmetz (R' Mordechai Appel's new son-in-law). The צאן קדשים (children) helped, serving as משוררים with their sweet voices.

On ראש השנה afternoon, after praying for a good year for themselves and all of כלל ישראל, the Jews of Sitchel went to the Iza River for תשליך.

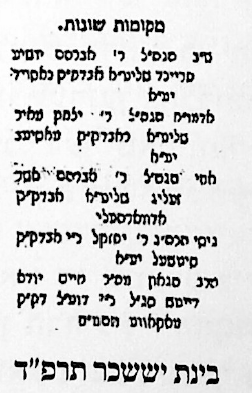

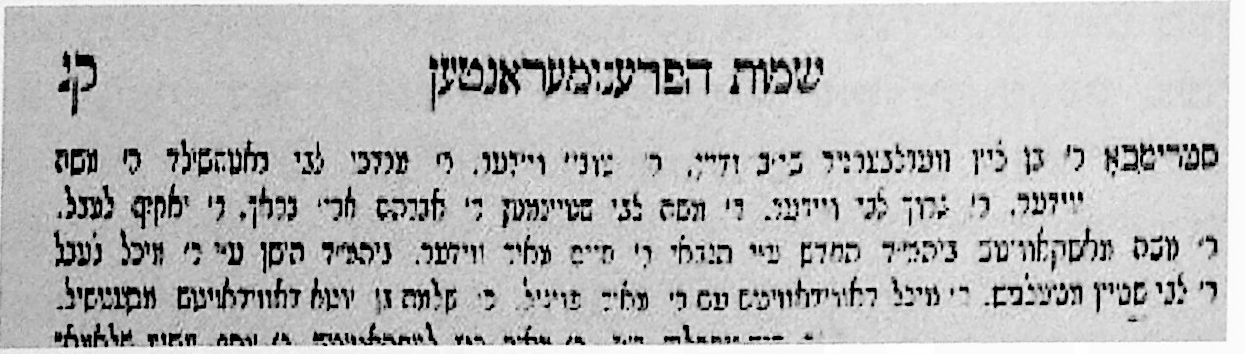

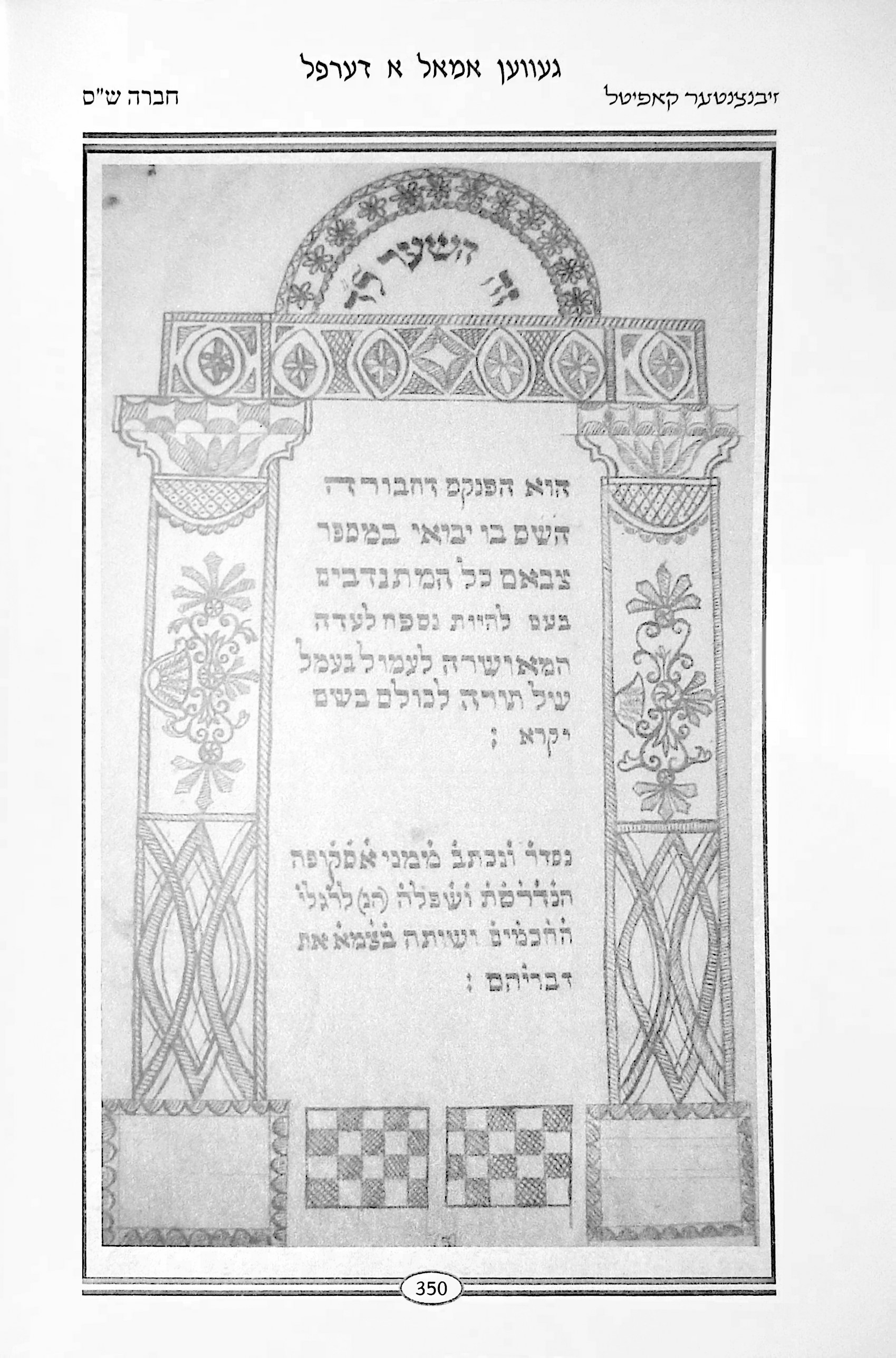

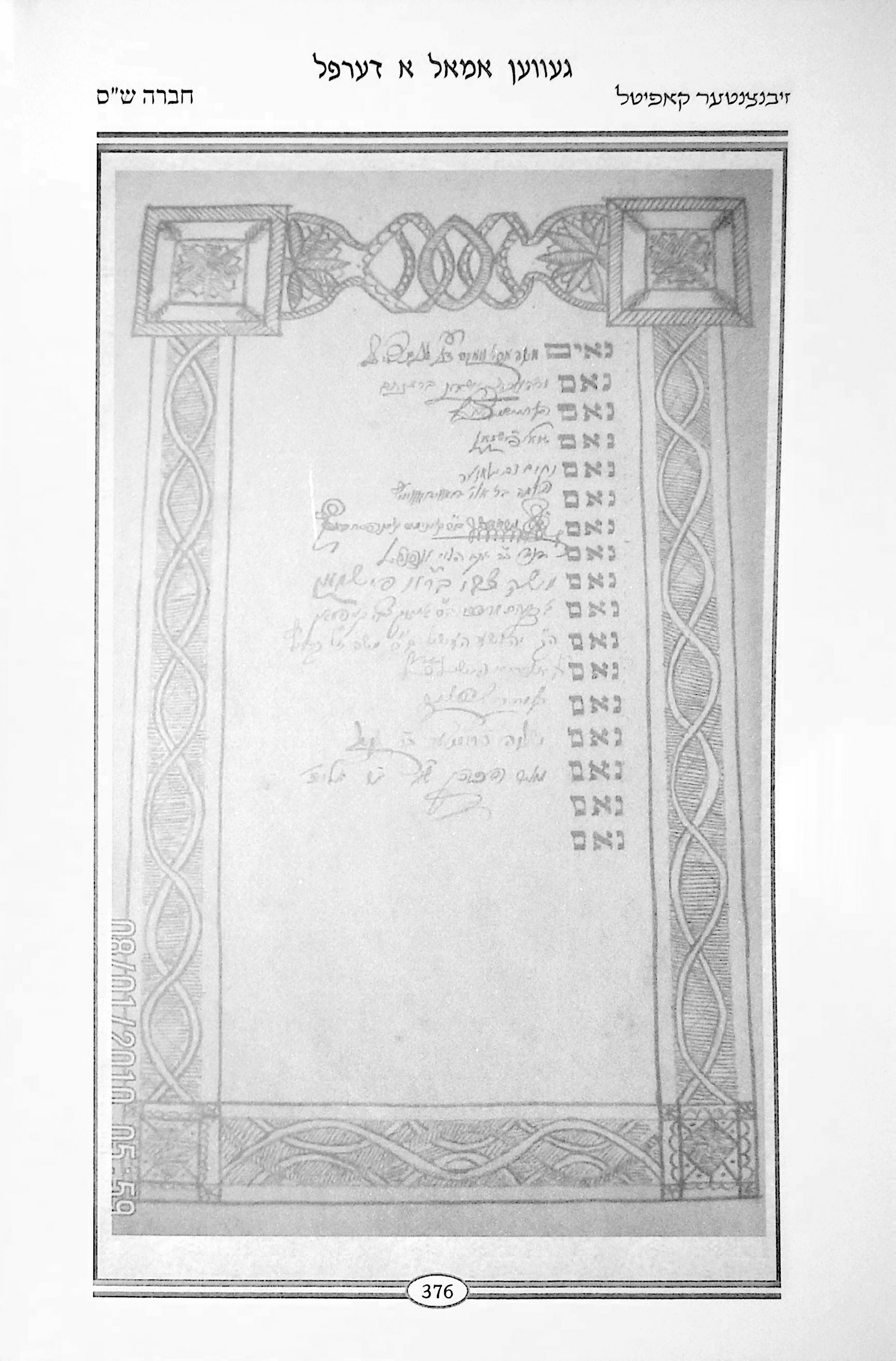

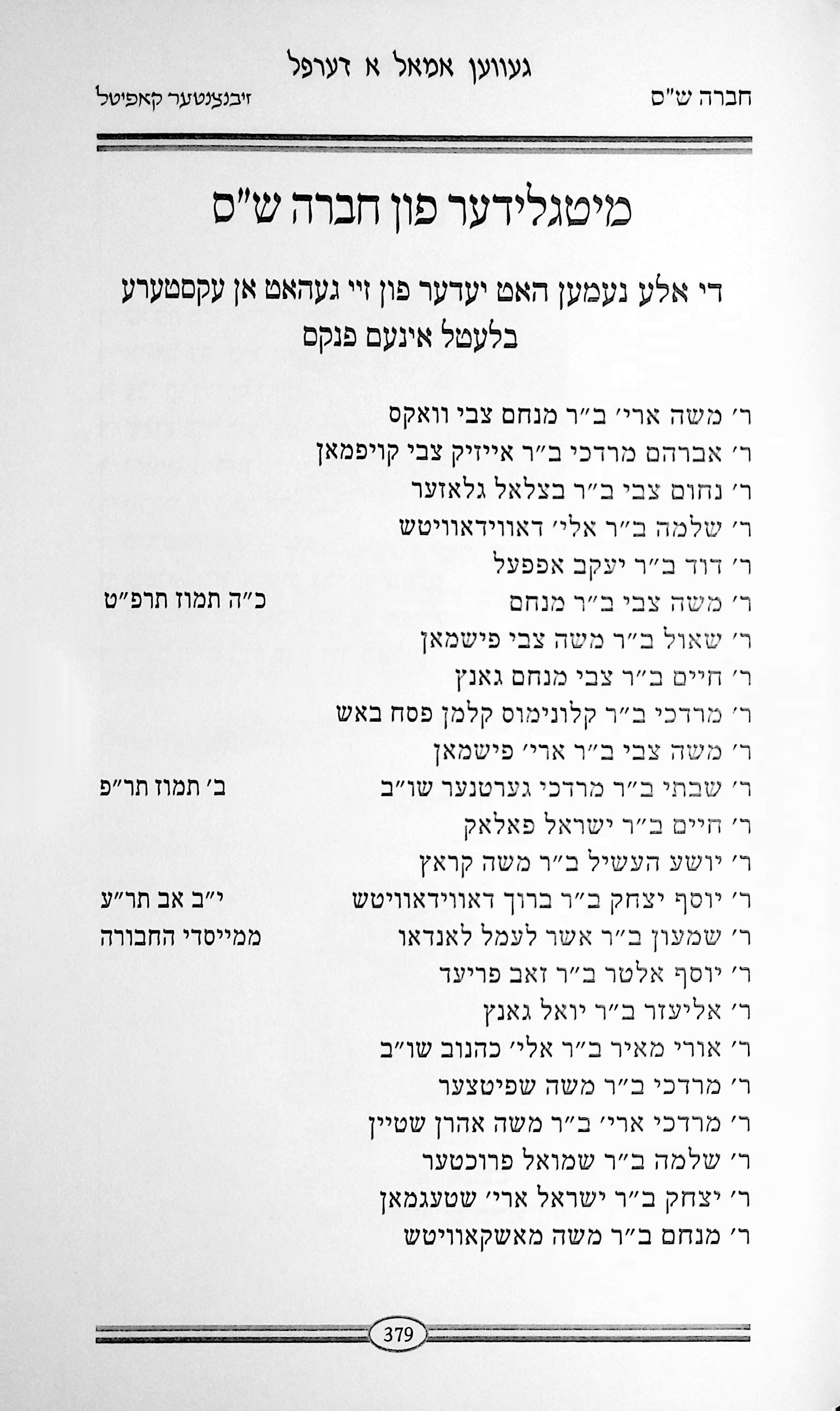

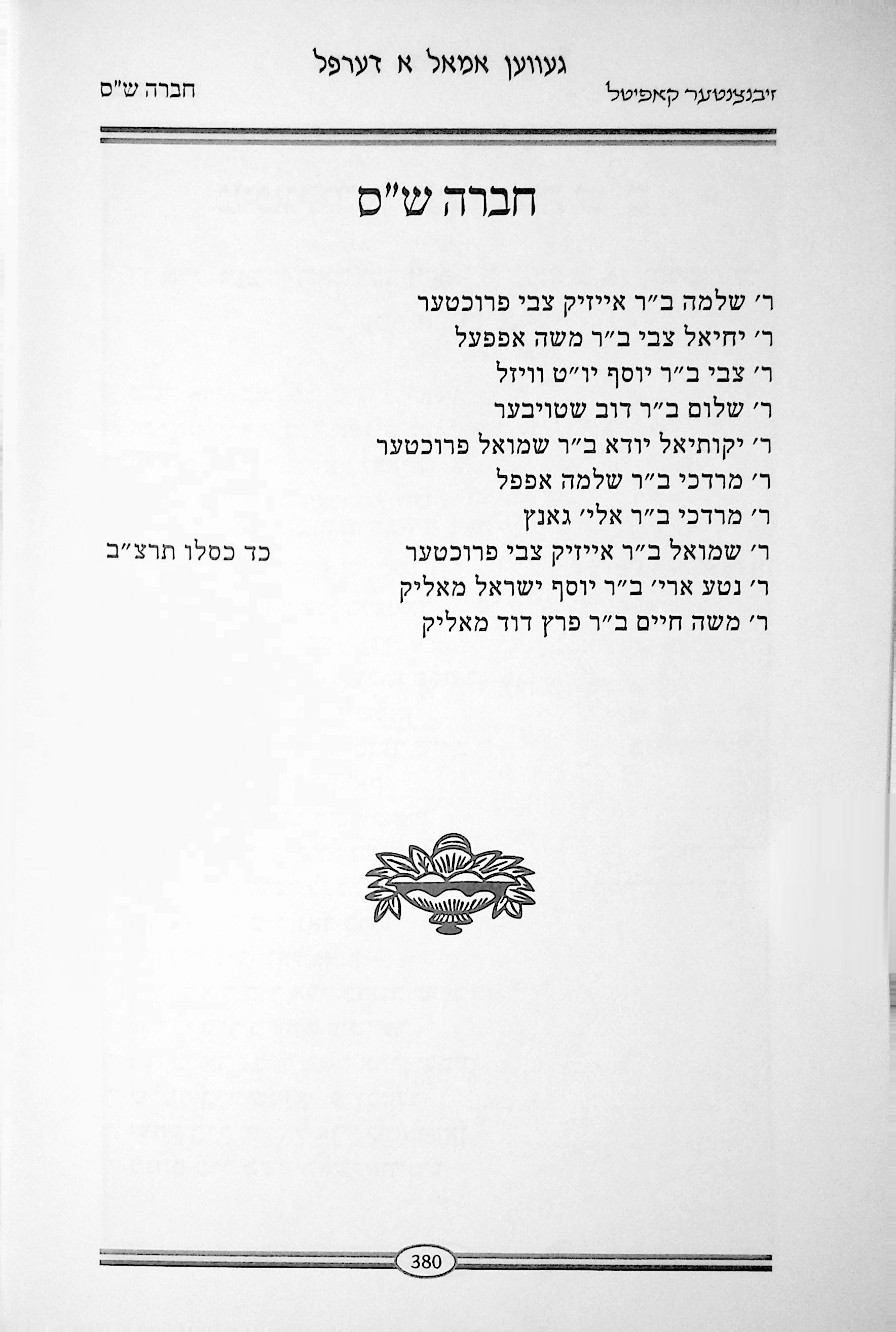

List of signatories

With the arrival of שלש עשרה מדות, serious preparations began for the holiest day of the year. Every woman prepared her own wax candles. Wax was purchased from beehives and melted down to fashion candles large enough to burn for over 26 hours. Two such candles were made: a "Healthy Candle" for the living, and a "נשמה Candle" for parents in גן עדן.

Supplication for Candle Making Erev Yom Kippur *)

This תחינה should be said when making the candles on ערב יום כיפור:

"Master of the World, I beg You, O very Merciful God, accept my מצוה of these candles..." [The rest of this techina is unfortunately cut off in the book.] While making the candles, they offered a fervent prayer with great weeping.

*) The custom in earlier times was for righteous women to make the candles themselves in honor of יום כיפור. They made the wicks and dipped them. Among the צדיקים of the House of Belz, the custom was to deliver a fiery sermon to the women while they made the candles, awakening them to תשובה. The awakening among the listeners was immense, and their weeping reached the very heart of Heaven.

The entire procedure was accompanied by hot tears and תחינות. With every wick she dipped, the woman mentioned זכות אבות, listing Noach, Avraham, Yitzchok, Yaakov, and onwards, begging with tears that their merit should protect her, her husband, and her children.

Which candle to take to shul was a matter of old debate. Since most אחרונים hold that the נשמה candle should be lit in shul—"may one be healthy at home," as they phrased it—everyone's נשמה candles were lined up in the בית המדרש. On מוצאי יום כיפור, each Jew took home whatever remained of his candle.

Very early on ערב יום כיפור, people stood in line by the שוחט with their chickens. The meat still had to be plucked, salted, and cooked in time for the סעודה המפסקת.

Succos

A סוכה in the אלטער היים was cobbled together from boards of all types, sizes, and colors—whatever wood one could lay a hand on. From the inside, the patchwork walls didn't matter; beautiful handmade decorations hid all the secrets.

For סכך, they used corn stalks. By autumn, the vegetables had been harvested, and the green, juicy stalks had dried into brown wood. Some gentile neighbors even donated their own dried stalks, watching the remarkable Jewish festival of huts with interest.

Architecture: The Corn Sukkah

In many parts of the world, evergreen branches are used for S'chach (roofing). In Maramureș, cornstalks were the standard. They were abundant after the harvest, grew straight (making them easy to lay across the roof), and provided excellent shade. It reflects how Jewish law adapted to the local agriculture.

AI GeneratedSimchas Torah

שמחת תורה marked the official end of the mild autumn, inviting the cold winter to take its place. But the approaching frost couldn't dampen the joy enveloping the village. The very earth seemed to lift under their feet, throwing the inhabitants into the air in joyous dances.

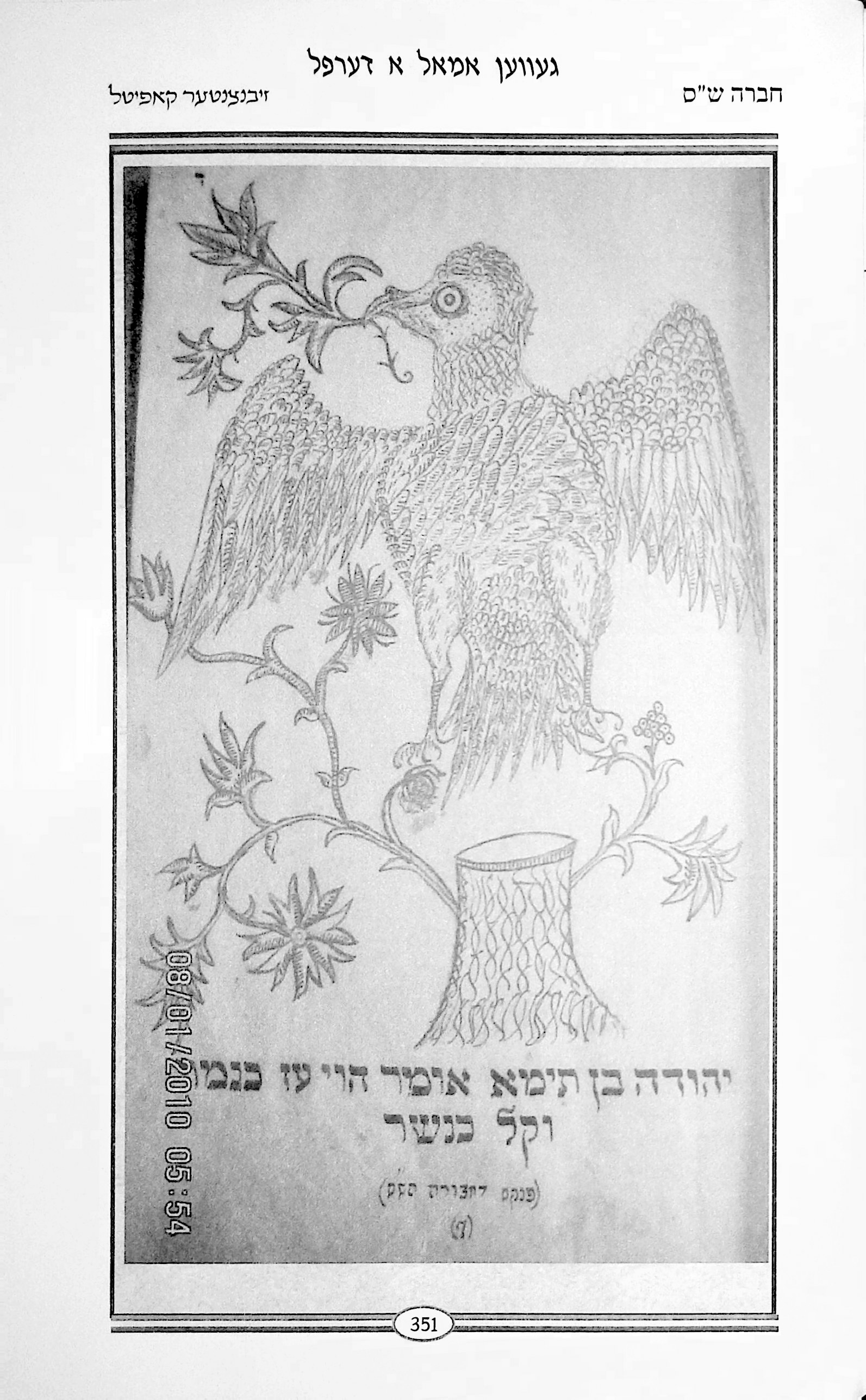

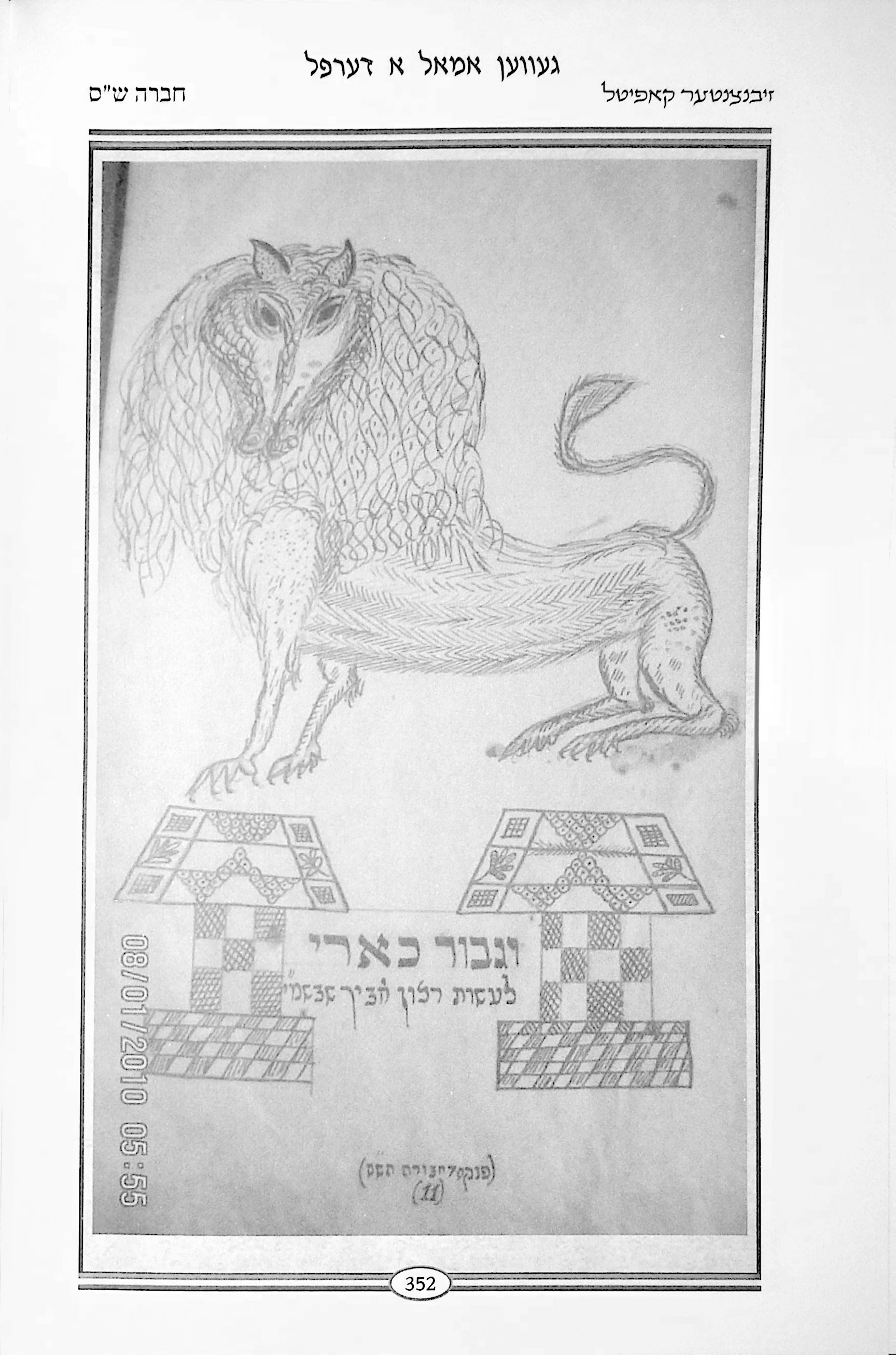

A special enthusiasm reigned among the "ש"ס אידן"—the תלמידי חכמים of Sitchel who shared a deep bond with the תורה הקדושה. R' Avigdor Moshe Fried, a distinguished local למדן, stood out in particular, dancing in a spirit elevated לעילא ולעילא. The honor of the sixth הקפה, "עוזר דלים," was sold to raise funds for the בית המדרש. The happy בעל הבית who won this privilege felt he had no equal in the world.

At the end of the dancing, when spirits were high and the merriment reached its peak, the שמש would announce the arrival of winter with a humorous proclamation:

"רבותי, everyone should hang themselves!

Hang as many grapes in the attic to dry into raisins.

Hang beef in the chimney so we can have good smoked meat.

Hang as many beads around the neck.

"Then, everyone should bury themselves in the earth!

Bury as many potatoes in the earth to store for winter.

Bury as many carrots in the earth.

And above all, do not forget to prepare enough wood for heating!"

He would conclude with a smile, "All this applies only to he who has. He who has not is exempt from it all."

Seasonal Cycle: The "Burying" Rhyme

This rhyme wasn't just a joke; it was a survival checklist. "Burying" refers to the Root Cellars. October (Simchas Torah) was the absolute deadline to get crops underground before the frost hit. If you missed this window, your potatoes would freeze and rot, leading to starvation in January.

AI GeneratedWinter

Potatoes stored for the long winter

When the leaves began to change color, a shudder went through one's bones. It brought the reminder of the approaching European winter, a season that evoked anxiety among Sitchel's residents. With the village's minimal defenses, one had to rely on רחמי שמים that the frost wouldn't cause serious illness or fatalities, רחמנא ליצלן.

On the first day of autumn, people began inspecting their homes for necessary repairs. Windowpanes were checked for cracks and tightly nailed or sealed. A draft that felt refreshing in July would be a cruel intruder in January.

Thatched Roofs

The straw roofs required special attention. If the straw was too thin, buckets of rain would soak the house, ruining clothes, wooden furniture, and the chest under the bed—not to mention freezing the inhabitants to the bone. Those with dirt floors had to be especially careful, as water meant their home would turn into a mud pit.

Architecture: Thatched Roofs

Straw roofs were cheap and provided great insulation, but they required constant maintenance. They were also a fire hazard and a home for rodents. In the spring, it was common to see birds pulling straw out of the roof to build nests, forcing the owner to patch it up before the next rain.

AI Generated

Stockpiling wood for heating and cooking was the most critical task. The wealthy ensured they had enough fuel to last most of the winter, while the poor scraped together every penny to buy whatever wood they could afford.

If the cold arrived late, the villagers rejoiced at the reprieve. But they knew without a doubt that winter would eventually seize its throne, ruling the village with wind, snow, and frost.

European winters were always bitter, but in a hard year, the frost was unbearable. Snow could pile up several feet high, blocking front doors completely. Families sat trapped inside for days, waiting for the sun to melt the icy walls besieging them.

Chanukah

The spark of joy in those long, freezing nights was חנוכה. Unlike today, where we associate חנוכה with dairy, in the village it was a festival of meat. Dairy was a year-round staple, but meat was a luxury usually reserved for שבת. חנוכה was the time to slaughter geese, rendering their skin to make schmaltz for פסח.

Culinary History: The Goose Festival

Why was Chanukah associated with geese? In December, geese are at their fattest before the deep winter sets in. It was the perfect time to slaughter them to harvest the fat (Schmaltz) which was essential for cooking during Passover when oil was forbidden or hard to get. The "Gribbenes" (cracklings) mentioned next are the crispy byproduct of rendering this fat.

AI GeneratedSince meat couldn't be stored long-term, it had to be cooked and eaten immediately, to the boundless delight of the children. Sitting by the light of the brass מנורה, the family feasted on hot, fresh meat and fatty גריוון. The tiny flames spread warmth through the house and hearts, a reminder that even in dark times, there is a glow of hope.

Pesach Preparations

Cleaning the small Sitchel houses should have taken no more than a week, but custom dictated that פסח preparations begin immediately after פורים. ספרים were placed in the yard to air out, with the breeze carrying away the dust. Clothes and blankets were hung outside to freshen up. Copper pots were scrubbed until they gleamed, then taken to the Iza River for a thorough washing. Dishes reserved for פסח underwent a *kashering* procedure with boiling water. The house was scrubbed, and walls were whitewashed a fresh snow-white.

Hygiene: The Annual Whitewash

Whitewashing the walls wasn't just for looks; it was a sanitation measure. "Whitewash" is made from lime (calcium hydroxide), which is a mild disinfectant. Recoating the walls every Spring killed bacteria, insects, and mold that had grown during the damp winter.

AI GeneratedWeeks before יום טוב, parents checked who needed trousers, a suit, or a shirt, visiting the tailor to place orders. Those who could afford it ordered new shoes for their children; others had the cobbler repair old ones.

The Sichel Matzah Bakery

Sitchel had its own מצה bakery to serve the community. The owner, R' Peretz Dovid Malik, allowed locals to bake their מצות close to home. The village Rav, HaRav HaGaon R' Yechezkel Widman, would store his מצות in a pillowcase hung on the wall until פסח. On ערב פסח, the Rav took responsibility for ensuring that not a single Jew in his community faced the holiday without the essentials—מצות, wine, and schmaltz.

Daily Life: The "Pillowcase" Pantry

Why hang Matzah in a pillowcase? In small village cottages, there were no built-in pantries or cabinets. To keep the Matzah safe from mice and moisture (and away from children), hanging it high up on a nail in a clean pillowcase was the standard storage solution. It reflects the extreme simplicity of the furniture in these homes.

AI GeneratedOn אחרון של פסח, the day of יזכור, people visited the home of the גבאי of the חברה קדישא. After enjoying some preserves, the village Jews took to the streets in joyous dance. Traffic stopped, and passing gentiles stepped aside with respect for the Jewish celebration.

As hard as it was to bring in the יום טוב, parting with it was harder. They dragged out the final hours, delaying the end as long as possible. The heart refused to let go of this beautiful, peaceful time and return to the burdens of the year. They davened מעריב slowly, wishing one another a healthy summer, and singing with longing:

"טייערע ברידער, הארציגע ברידער, ווען וועט מען זיך נאכאמאל זען? אז גאט וועט געבן, געזונט און לעבן, וועלן מיר זיך נאכאמאל זען..."

(Dearest brothers, sweet brothers, when will we see each other again? If God grants health and life, we will see each other again...)

Chapter Four — The House of Kosov-Vizhnitz

The House of Kosov-Vizhnitz

Much like the surrounding communities in the Maramureș region, the Jewish community in Sitchel did not succeed in appointing a רב to stand at its helm during its early years. For a long period—spanning over a hundred years, from 5560 (1800) until 5682 (1922)—the village of Sitchel stood without an official spiritual leader. The שוחטים generally occupied the position of דיין as well, supervising the כשרות, the עירוב, the מקוה, and all other Jewish affairs.

Leadership: The "Multi-Tasking" Shochet

In small villages that couldn't afford a full-time Rabbi, the Shochet (slaughterer) became the de facto spiritual leader. Because he was already required to be a scholar to understand the complex laws of Shechita, the community relied on him for all Halachic questions, from marriage to burial. He was the "Swiss Army Knife" of Jewish functionaries.

AI GeneratedThe change in this phenomenon came about through the faithful shepherd of European Jewry, the רבן של ישראל, Rabbi Yisrael בעל שם טוב zy"a. The holy Baal Shem once traveled from Kitev, a city near the Carpathian Mountains, and strolled up to the mountain peaks accompanied by his חברייא קדישא. Upon reaching the top, a long conversation ensued among the holy צדיקים, interwoven with דברי תורה and hidden secrets (רזין דרזין).

Geography: The Cradle of Chassidus

The Carpathian Mountains were not just a backdrop; they were the incubator of the Chassidic movement. The deep isolation of these peaks allowed early mystics like the Baal Shem Tov to meditate in solitude (Hisbodedus) undisturbed.

AI GeneratedSuddenly, the בעל שם טוב became pensive and stood lost in thought. The gaze of his holy eyes was directed toward the Maramureș region, which lay at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains on the other side. The disciples immediately stopped their conversation in awe, and a deathly silence descended upon the desolate place. None of the חברייא dared to disturb the Rebbe's thoughts or ask what had captured his attention.